Iran has a rich history of religions, reflecting its ancient history and vibrant culture. Dominated by Shia Islam, the nation’s spiritual life also preserves the teachings of Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest faiths. Additionally, Sunni Islam, the Baha’i Faith, and various indigenous beliefs contribute to this diverse religious landscape. This article will cover the history of Iranian religions, provide a brief timeline, and a summary of the most important Persian religions before Islam.

Iranian Religions List

| Religions & Beliefs | Dates of Origin | Point of Origin | Current Status | Estimated Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive Beliefs | Prehistoric times | Iran (various regions) | Practiced in ancient times; largely replaced by organized religions | N/A |

| Mithraism | c. 2nd century BCE – 4th century CE | Persian Empire | In decline after the rise of Christianity; historical significance | N/A (extinct) |

| Zoroastrianism | c. 1200 BCE | Ancient Persia (modern-day Iran) | Once the state religion; now a minority religion | ~25,000 |

| Anahitaism | c. 2000 BCE | Ancient Persia | Practiced in antiquity; now largely obsolete | N/A (extinct) |

| Mazdakism | c. 5th century CE | Persia | Influential briefly, advocating communalism; largely extinct | N/A (extinct) |

| Zurvanism | c. 4th century BCE | Persia | A dualistic belief system largely absorbed into mainstream Zoroastrianism | N/A (extinct) |

| Manichaeism | c. 3rd century CE | Persia | Flourished in ancient times, faced persecution, largely extinct | N/A (extinct) |

| Judaism | c. 6th century BCE | Ancient Persia | Continuous presence since antiquity; small community | ~8,500 |

| Christianity | 1st century CE | Roman Empire | Established early communities; currently a recognized minority | ~300,000 |

| Islam (Shia) | 7th century CE | Arabian Peninsula | Predominantly Shia; state religion | ~80 million (total in Iran) |

| Islam (Sunni) | 7th century CE | Arabian Peninsula | Minority status; primarily among ethnic groups | ~5-10 million |

| Baha’i Faith | 19th century CE | Persia (modern-day Iran) | Persecuted; not officially recognized | ~300,000 |

| Yarsanism | c. 14th century CE | Western Iran | A syncretic belief system; recognized in some regions | ~1 million |

| Druze | 11th century CE | Middle East (including Iran) | Small community in some regions; not widely practiced in Iran | ~1,000 |

| Babism | 19th century CE | Persia | Precursor to Baha’i Faith; faced persecution | N/A (extinct as a distinct movement) |

| Behafaridians | 19th century CE | Persia | A sect influenced by Babism, no longer a prominent group | N/A (extinct) |

Ancient Iranian Religions and Rituals

The first ancient Iranian religious figurines discovered in the country date back to the Neolithic age. Among the oldest figurines, a clay figurine was discovered in Tepe Sarab named “Venus of Tepe Sarab.” Due to the exaggeration and enlargement of the female features of this figurine, a sign of emphasis on reproduction and fertility, it was assumed that this figure had a ritualistic function.

Other female figurines similar to the Venus figurine have been found in the Near East. These figurines, both those that were discovered from Tepe Sarab in Kermanshah and those that were found in “Çatalhöyük” and “Hacılar” in present-day Turkey, show the presence of abstract concepts and religious beliefs in the people of that period. These figurines, which are the oldest evidence of Iranian religions, have been discovered among the remains of early Sedentism and ancient civilizations of the Near East, which dated back to around 4,000 to 6,000 years ago.

Elamites believed in a great god called “Inshushinak” and built temples to worship and sacrifice for their god. Dūr Untaš Ziggurat, which is known as Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat, is one of the historical remains of the Elamite era. According to some orientalists, this temple is the oldest religious building in the history of Iranian religions.

The Elamites worshiped snakes; Praising the snake was rooted in their belief in primordial magic. The image of the snake on the lids of dishes and pots granted protection against bad intent and evil forces. The snake figure was also carved on the gates, altars, and the scepter of Elamite kings.

The Scythians were highly civilized, had strong religious beliefs, and believed in a heavenly power. However, they also worshipped different idols.

Most Famous Ancient Iranian Religions

Some Iranian religions spread beyond their origins and were practiced throughout the world over the years. The followers of these religions have left behind remarkable architectural works and books. This is a brief description of these world-famous Iranian religions:

Mithraism

In the past, humans were terrified of darkness and cold, and the faint glimmers of the sun rising from behind the mountains signified the promise of light, warmth, and food. This is why primitive humans began worshipping the sun. Mithraism, or Mehrism, is one of the Iranian religions centered around sun worship and is deeply rooted in Iranian beliefs. It is mentioned in the Avesta has heavily influenced Zoroastrianism, and some of its beliefs can be found in social traditions.

Mithra is an influential and powerful mythical figure born from the core of a stone. He is the custodian of loyalty, covenant, light, home, and motherland. In Mithraism, it is believed that Izad (god) Mithra went to the sky on his chariot of the sun and will return one day to reshape the world.

Origins: Mithraism originated in Persia (modern-day Iran), with deep connections to earlier Iranian sun worship practices.

- Italy: The heart of Mithraic worship.

- Western Europe: Countries like Germany, France, and Britain had significant Mithraeums.

- Eastern Europe and the Balkans: Some evidence of Mithraism exists in these regions.

Primary Demographics: Mithraism was predominantly practiced by men, especially soldiers and merchants, and was often viewed as a male-dominated mystery religion.

Influential Classes: It attracted military members, as Mithras was associated with qualities valued in warfare and loyalty.

Civic Influence: While initially appealing to lower and middle classes, it garnered interest among the Roman elite during the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE.

Worshipping Anahita or Venus

Anahitaism, or worshipping Anahita, is an ancient Iranian religious ritual. Water is one of the natural elements in traditional Iranian belief, which Iranians hold in high esteem. Anahita is the goddess of water and the guardian of all water on earth. This goddess is also highly praised in The Avesta’s prayer Hymns. Anahita blesses wealth, house, tribe, life, the universe, kingdom, and the motherland. In the sixth verse of “Aban-Yasht”, Ahura Mazda states that he created Anahita to develop the land and tribe and maintain and guard the waters.

During the Achaemenid period, temples were built in honor of Anahita, such as the Anahita temple at Bishapur and the one in Kangavar. People were praising the goddess of water next to their fields and asked her to bless their fields with rainfall.

Zoroastrianism

When the Aryan tribes in Iran transitioned from their herding and nomadic lifestyle to Sedentism, Zoroaster emerged as a reciter of religious poems. Zoroaster sought to change people’s perspectives and encourage them to worship the one true God. He opposed animal sacrifice, believing it was the cause of the herders’ poverty.

In the religion of Zoroastrianism or Mazda-Yasna, one of the most well-known Iranian religions, Ahura Mazda is the great creator of the world and the source of all goodness. He is in constant conflict with Ahriman, who symbolizes evil and destructive intent. Zoroaster believed in this idea: “There is only one path in the world, and that is the path of righteousness.” This Iranian prophet urges his followers to practice good thoughts, words, and deeds.

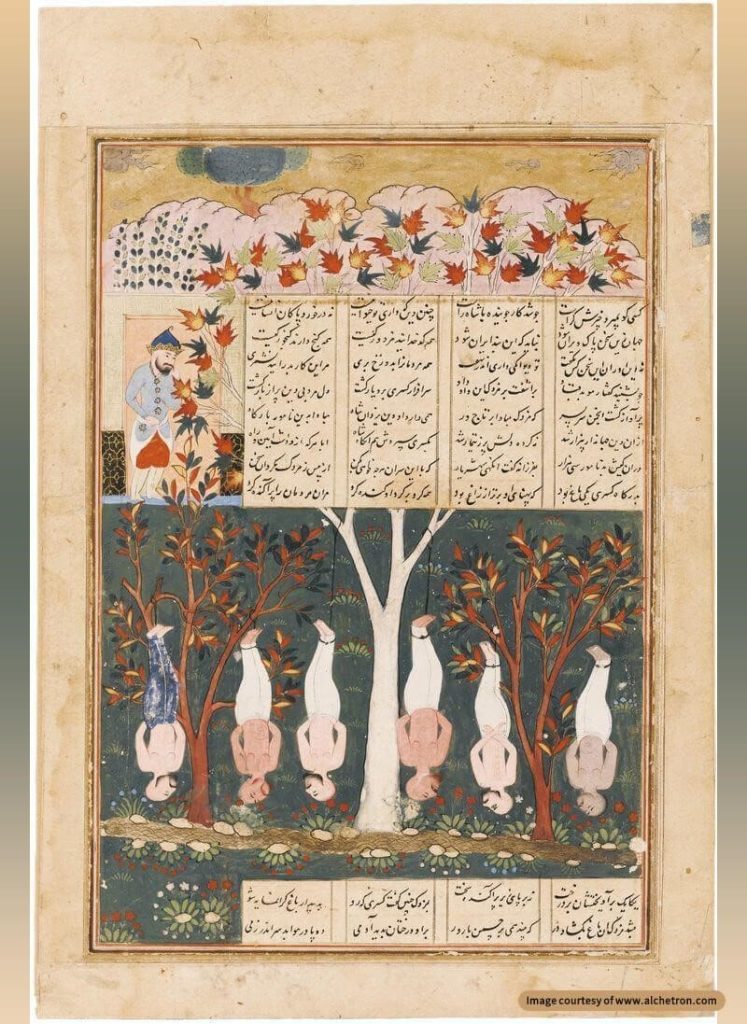

Mazdakism

The Mazdak religion is another example of ancient Iranian religions. Mazdak Bamdadan was more of an activist and social reformer than a prophet, and he himself never claimed to be a prophet. The religion of Mani or Manichaeism inspired Mazdakism. Before him, a Mobad (priest) named Bundes founded a faith based on Mani’s religion, and Mazdak followed in his footsteps.

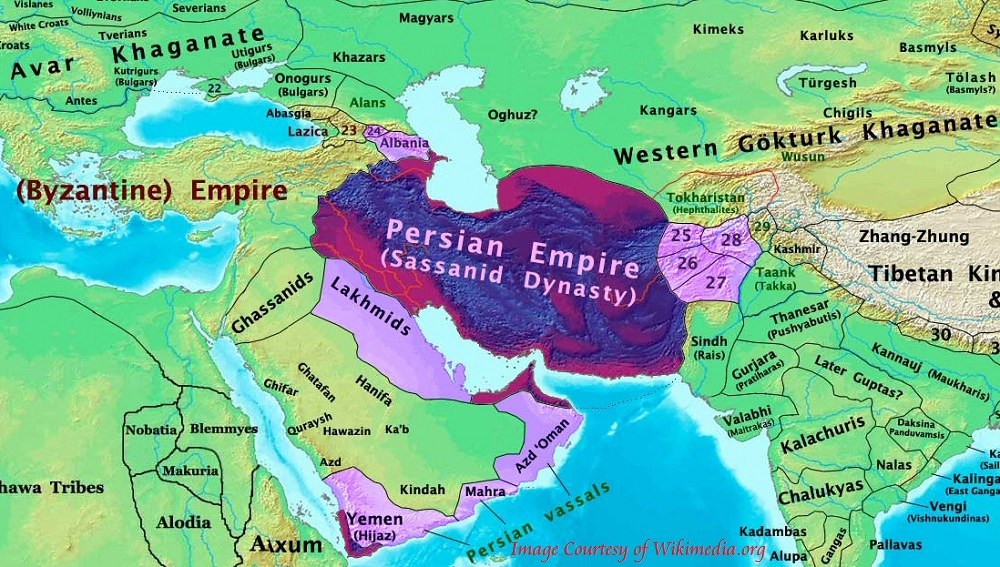

Qobad or Kavad I, the Sassanid king at the time, afraid of the growing influence of the priests and nobles and wanting to regain his power as king, supported Mazdak. Therefore, Mazdakism rapidly spread in the Sassanid empire. It even reached the Arabian Peninsula.

During that period, drought and famine drove the poor and angry to join Mazdak’s uprising. Mazdak believed that God had provided food for all people on earth, which should be divided equally. However, people had grown twisted and unkind to each other, forsaking the divine path. Thus, Mazdakism was an endeavor to reform social classes and dismantle the aristocracy.

- Origins: Mazdakism emerged in Persia, particularly within the Sassanian Empire, gaining traction as a significant ideological force.

- Influence Regions: Although primarily centered in Persia, Mazdakism influenced adjacent territories through:

- 4th-6th Century Sassanian Empire: The heart of the movement, where it directly shaped political and religious discussions

- Nearby Regions: Ideas and practices might have reached surrounding cultures, including parts of Central Asia, influenced by the expansion of Sassanian authority

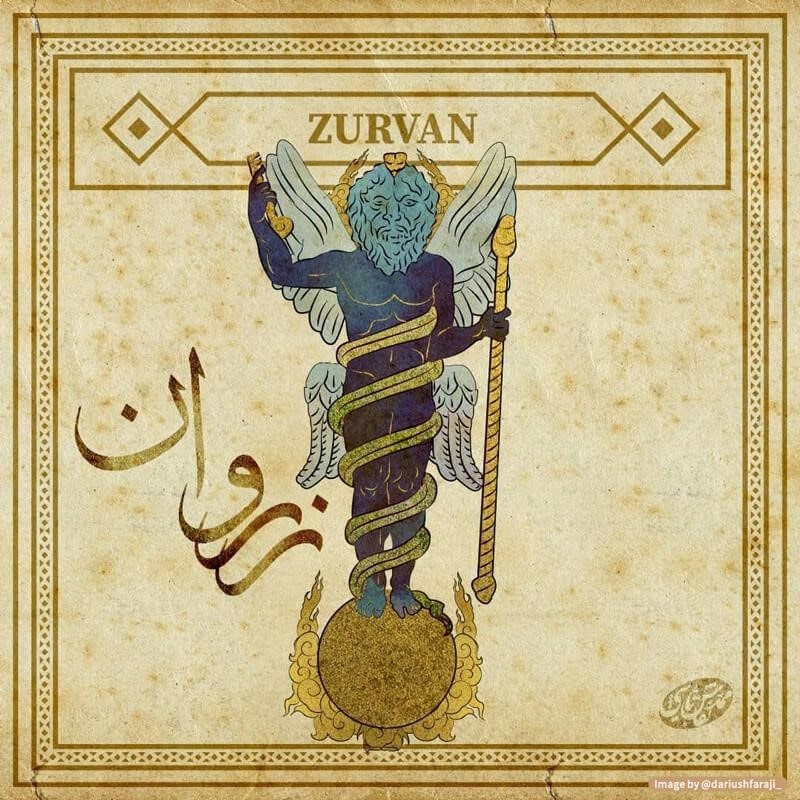

Zurvanism

Zurvan means time and is the name of one of the gods in ancient Iranian religions. Some believe that the Zurvanism religion originated from the Zoroastrian religion at the end of the Achaemenid period. However, some studies also claim that the Zurvanism religion has existed since the time of the Medes, and the Mogh or Magi implemented their beliefs in Zoroastrianism as well. Despite its decline, Zurvanism contributed significantly to debates within Zoroastrianism and influenced later religious and philosophical systems, including aspects of Middle Eastern and Gnostic thought.

- Origins: Zurvanism developed in Persia, primarily during the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) as a distinct sect of Zoroastrian thought.

- Areas of Influence: While predominantly based in Persia, its ideas influenced various regions, including:

- Mesopotamia: Interaction with nearby cultures and religious beliefs.

- Central Asia: Its teachings and elements likely spread through trade and cultural exchanges.

In the mythological narrative of Zurvanism, it is said that he had two sons: one of light and goodness, named Ahuramazda, and the other of evil and darkness, named Ahriman. These two brothers are constantly at war for world domination.

Manichaeism

Mani was an Iranian philosopher, poet, writer, Hakim (traditional doctor), and painter. Born to Iranian parents, he founded a religion combining Christian, Zoroastrian, Buddhist, and Gnosticism. He accepted everyone from every race and class.

Mani considered himself a prophet like Christ and the Buddha who presented a religion to people. Three major concepts from other religions influenced Manichaeism beliefs:

- Belief in the arrival of a savior figure, derived from Christianity

- Belief in dualism, influenced by Zoroastrian

- Belief in reincarnation from Buddhism.

The basis of Manichaeism, which is one of the widely recognized Iranian religions, is the belief in dualism. Mani believed in the god of light and kindness and that there was also a god of darkness. According to Mani, Man was created out of this duality of light and darkness, and he should try to cultivate his light side and avoid the dark aspects of his essence. The followers of Manichaeism are called “Din-avaran” or believers.

Mani was skilled in painting, and the book “The Arzhang” is a collection of his illustrations. Through these illustrations, he introduces the principles of his religion to his followers in a simple way. According to some researchers, Mani’s paintings are the first examples of Persian Miniature.

Behafaridians

The Behafaridians were followers of Behafarid, a Zoroastrian heresiarch and self-styled prophet who lived during the late 7th and early 8th centuries. Behafarid, whose name means “son of Farvardin,” claimed to have divine revelations and performed miracles to gain followers. His movement was primarily social, emphasizing practical and social reforms over spiritual and philosophical aspects.

Behafarid’s teachings attracted many Zoroastrians, particularly in the Nishapur region, where he began his mission. He claimed to have visited China and brought back miraculous objects, including a shirt and robe of green silk that he used to perform a staged resurrection, further convincing people of his prophethood.

Despite his initial success, Behafarid’s movement faced opposition from orthodox Zoroastrian authorities, and he was eventually executed around 748-49. His followers, known as Behafaridians, continued to practice his teachings for some time, but the movement eventually declined.

- Origins: The Behafaridian movement arose in Persia, particularly during the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE), a time of significant religious and philosophical evolution in Iran.

- Centers of Influence: The sect primarily thrived in urban areas of Persia, such as:

- Ctesiphon: As a key city and cultural hub of the Sassanian Empire, it likely served as a center for Behafaridian teachings.

- Other Urban Areas: Smaller towns and cities with Zoroastrian populations interacted with and absorbed Behafaridian ideas.

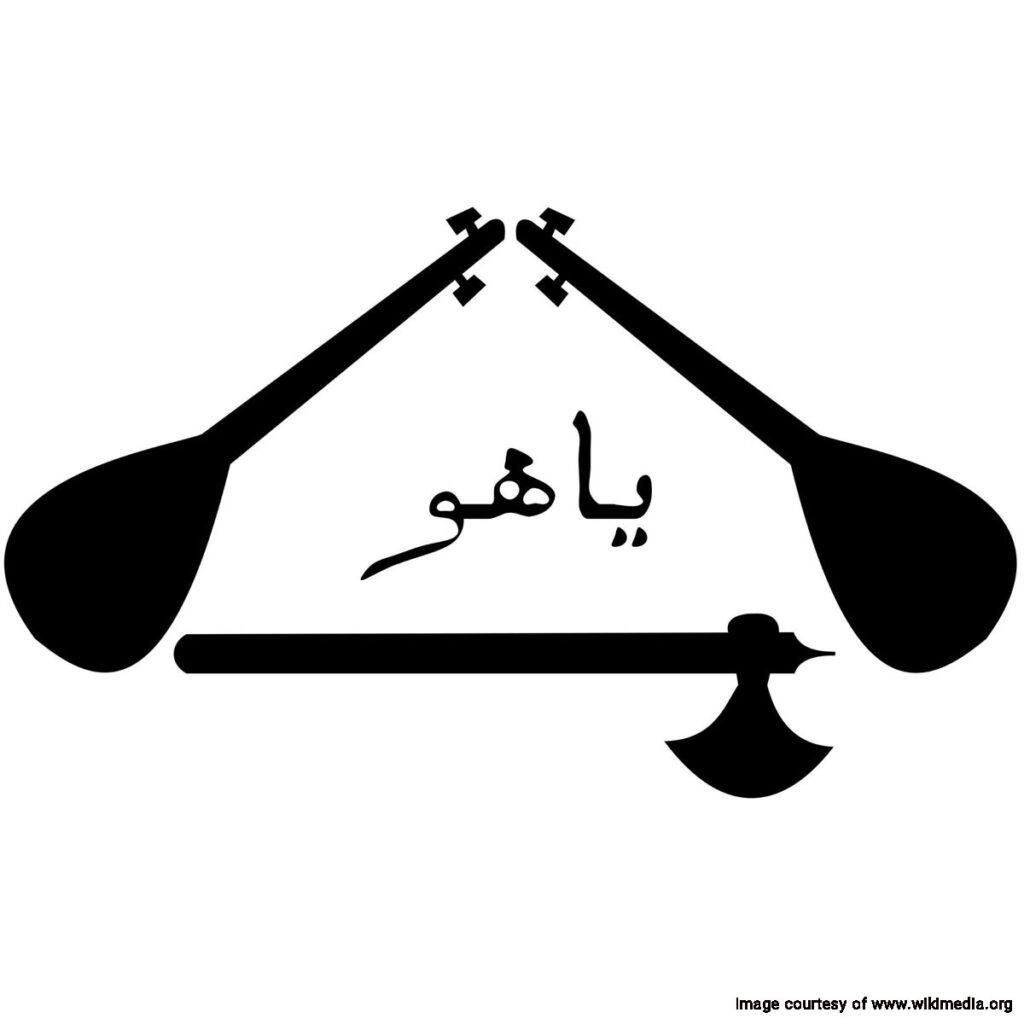

Yarsanism

The Yarsan, also known as Ahl-e Haqq or Kaka’i, is a syncretic religion founded by Sultan Sahak in the late 14th century in western Iran. The religion combines elements of Zoroastrianism, Islam, and local Kurdish beliefs, creating a unique and rich spiritual tradition.

Yarsanism emphasizes that “God is the first and the last.” Its followers believe in a series of divine manifestations, including Sultan Sahak, which is considered God’s final manifestation. The religion’s central text is the Kalâm-e Saranjâm, written in the 15th century, which outlines the teachings and beliefs of the Yarsan faith.

- Primary Regions: The majority of Yarsan followers are located in:

- Kermanshah Province: The heartland of Yarsanism in Iran.

- Lorestan and Ilam Provinces: Adjacent areas where Yarsani communities reside.

- Demographic Composition: Followers are predominantly Kurds, affiliated with tribes such as:

- GuranSanjâbiKalhorZangana

- Jalalvand

- Other Populations: Yarsanism also has followers in:

- Iraqi Kurdistan

- Turkic-speaking communities in Iran

Yarsanism is known for its mystical and esoteric practices, including using the Tambur (a sacred drum) during religious ceremonies. Yarsanis face challenges, including discrimination and pressure to assimilate into the dominant Islamic culture. Many Yarsanis practice their faith discreetly to avoid persecution. The community strongly emphasizes mystical and esoteric practices, including the use of the Tambur (a sacred drum) during religious ceremonies.

Despite facing persecution and pressure to convert to Islam, the Yarsan community has managed to preserve its unique religious identity and traditions over the centuries.

Druze

The Druze religion, also known as Druzism, is a monotheistic and Abrahamic faith that emerged in the 11th century in Egypt as an offshoot of Isma’ilism, a branch of Shia Islam. It was founded by Hamza ibn Ali ibn Ahmad and Muhammad bin Ismail Nashtakin ad-Darazi, who played significant roles in its early development.

The Druze faith is characterized by its syncretic nature. It incorporates elements from various religious traditions, including Zoroastrianism, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, and Pythagoreanism. The central text of the Druze faith is the Epistles of Wisdom (Rasa’il al-Hikma), which outline the religion’s core beliefs and doctrines.

Druze beliefs include the concepts of theophany (the manifestation of God in human form) and reincarnation (the soul’s cycle of rebirth). They believe in God’s unity and the soul’s eternity, and they hold several historical figures, such as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, and the Isma’ili Imam Muhammad ibn Isma’il, in high regard as prophets.

Divisions within the Community:

- Uqqal: The initiated members knowledgeable about the Druze faith’s esoteric teachings. They serve as spiritual leaders and guides for the community.

- Juhal: The uninitiated members who focus on worldly matters and do not possess the same level of spiritual knowledge or leadership roles.

Primary Regions: The Druze are primarily located in:

- Jordan: Smaller populations are found here as well.

- Lebanon: A significant population, particularly in the mountainous areas.

- Israel: Notable Druze communities exist, particularly in the Galilee and Golan Heights.

- Syria is another major Druze center, with communities primarily in the southwestern region.

Presence in Iran: In Iran, the Druze are mainly concentrated in:

- Kermanshah and Lorestan Provinces: These regions host the majority of the Iranian Druze population.

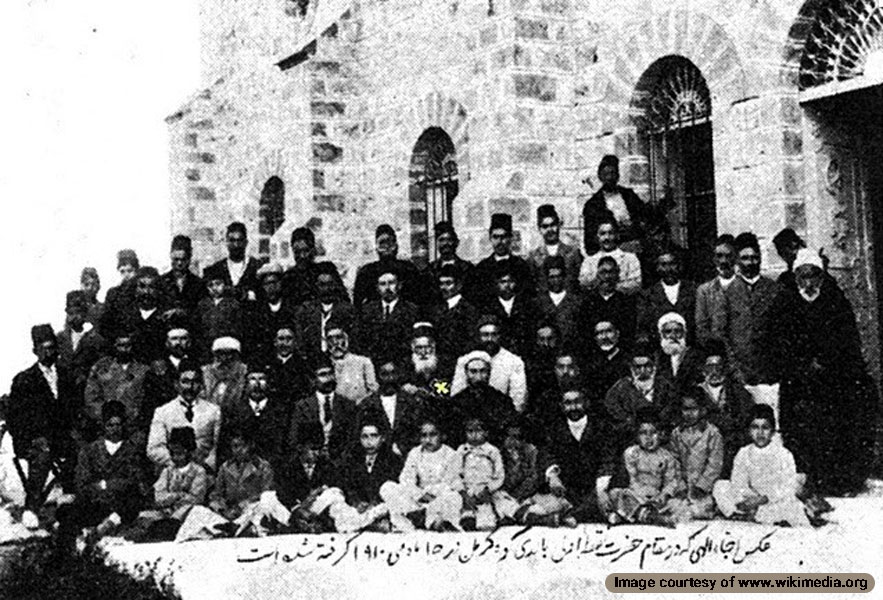

Bábism

Bábism, also known as the Bábi Faith, is a monotheistic religion founded in 1844 by Sayyid `Alí Muḥammad Shírází, who took the title the Báb (meaning “the Gate”). The Báb proclaimed himself the gate to the Twelfth Imam of Shia Islam and later declared himself to be a Manifestation of God, a status equal to that of prophets like Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad.

- Legacy: Bábism evolved into the Bahá’í Faith, with the Báb regarded as a precursor to Bahá’u’lláh, whose teachings continue to inspire social reform and spiritual unity today.

- Social Principles: Bábism promoted the abolition of clergy, universal education, and the elevation of women’s status.

- Manifestation of God: The Báb claimed to be the gate to the Twelfth Imam of Shia Islam and later asserted his status as a Manifestation of God, akin to prophets like Moses and Jesus.

- New Calendar: Introduced a unique calendar with 19 months of 19 days, replacing the traditional Islamic calendar.

- Persecution: Following the Báb’s execution in 1850, his followers faced severe persecution from the Qajar dynasty and Shia clergy, leading to many deaths and exiles.

Iranian Religions Throughout Different Historical Periods

Iranian religions have emerged and evolved in Iran throughout many historical periods. Religions embody essential aspects of the cultural growth and beliefs of Iranians. People of Iranian origin have either founded Iranian religions or have been influenced by Iranian culture, as Iranians have played a large role in the development and expansion of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Iranian Religions in The Indo-Aryan Migration

Ancient Aryan beliefs, as evidenced by mythological literature, the Avesta, and stone inscriptions, reveal a complex religious landscape characterized by a polytheistic worship system. Key aspects include:

- Nature of Deities:

- Bagh: Meaning “benevolent,” indicating their protective nature.

- Ahura: Meaning “Lord,” representing influential, divine figures.

- Amsha: Meaning “immortal,” referring to eternal beings associated with creation.

- Ritual Practices:

- The Aryans engaged in animal sacrifices, accompanied by hymns and prayers, to seek favor from their gods.

- Temples and Worship:

- Unlike the settled civilizations of Elam, Mesopotamia, and Greece, the Aryans did not construct grand temples. Instead, their worship was often more integrated with nature, honoring elements like water, earth, fire, and wind.

- Cosmic Dualism:

- They believed in “divine beings” who bestowed natural gifts, primarily light and rain, and “evil beings” who contested the divine, obstructing human happiness.

- Ethical Framework:

- Aryan religions promoted ethical values, emphasizing harmony with principles of honesty and integrity, suggesting a moral framework more pronounced than that found among the Babylonians and Assyrians.

These beliefs laid the foundation for later religions in Iran.

The following examples are some of the gods who were worshipped during the nomadic era and sometimes after Sedentism became popular among the Iranian people:

- Mithra, the god of covenant and the sun and order and justice

- Bahram or Varahram, the god who conquered the Div (devil) and the granter of victory for warriors

- Anahita, the goddess of water

- Tishtar or Tir, god of rain

- Zurvan, the god of time

Key Points about Ancient Persian Religions

- Natural Source of Deities: Most Aryan gods were associated with natural elements, embodying forces such as light, water, and fertility.

- Rituals and Transformations: Worship rituals were closely linked to natural transformations, including:

- Day and Night Cycles: Celebrating the transition between light and darkness.

- Seasonal Changes: Marking the seasonal shifts, which were vital for agricultural societies.

- Religious Calendar: A calendar was established to track religious festivals and prayer rituals, ensuring that celebrations aligned with natural cycles.

- Enduring Celebrations: Some ancient celebrations have persisted into modern times, including:

- Nowruz: Celebrated as the arrival of spring and the end of winter, symbolizing renewal and rebirth.

- Mehregan: An autumn festival honoring Mithra, the god of flocks, plains, and the sun, reflecting gratitude for harvests and the changing seasons.

Iranian Religions in the Median Era

The Medes, an Aryan tribe that settled in the western and central regions of the Iranian plateau, practiced a religion that evolved into a form of Mazdeism. Key aspects of ancient Median religion include:

- Mazdayazna: The term used by the Medes for worshipers of Mazda, reflecting their devotion to the god Ahura Mazda.

- Role of Priests:

- Mogh (Magi): The priests held a significant role in both religious and political spheres, acting as spiritual leaders and advisors to the king.

- Zurvanism:

- The predominant belief system of the Medes centered around Zurvan, the god of time, who was regarded as the highest divine entity. This focus on time distinguished their religious practices.

- Ritual Practices:

- Common rituals included singing hymns, performing religious prayers, and animal sacrifices, similar to other ancient Iranian religions.

- Transition to Zoroastrianism:

- Over time, as the Medes accepted Zoroastrianism, the Magi transitioned into Zoroastrian priests, integrating their earlier beliefs into the new religious framework.

The legacy of the Medes and their religious practices contributed to the development of Zoroastrianism, influencing the spiritual landscape of ancient Iran.

Iranian Religions in The Achaemenid Empire

Zarathustra, or Zoroaster, is believed to have lived toward the end of the Achaemenid era and is recognized as the prophet of Zoroastrianism, a significant Iranian religion. Key points about Zoroastrianism and the Achaemenid Empire include:

- Core Beliefs:

- Ahura Mazda: The ultimate god of creation and source of all that is divine, representing light and goodness.

- Ahriman: The embodiment of darkness and evil, constantly opposed to Ahura Mazda.

- Debate on Achaemenid Religion: Scholars have differing views on whether Zoroastrianism was the official religion of the Achaemenid Empire:

- Against Zoroastrianism: Scholars like Roman Ghirshman and Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob argue that the Achaemenids adhered to ancient Aryan beliefs, with Zoroastrianism having little influence during their reign. Zarrinkoob noted that the Magi, who performed religious rituals, did not practice Zoroastrianism.

- Pro-Zoroastrianism: Mary Boyce and others contend that Zoroastrianism was the official religion from the Achaemenids’ rise to power.

- Conversion After Darius: Scholars like Muhammad Dandamayev suggest that early Achaemenid kings were not Zoroastrians but converted after Darius ascended to the throne

- Religious Tolerance: Despite differing opinions on their official religion, the Achaemenids are noted for their tolerance towards other faiths. The Persian Empire allowed various tribes to coexist, respecting their cultures and beliefs.

- Cyrus the Great: The Cyrus Cylinder highlights his benevolent conquest of Babylon, where he honored the Babylonian god Marduk and freed Jewish captives, allowing them to return to Jerusalem and rebuild their temple. This act earned him the title “Messiah” among the Jews, marking a significant moment in Jewish history.

These elements illustrate the complexity of religious beliefs during the Achaemenid era and the enduring legacy of Cyrus the Great’s policies of tolerance and respect for diverse faiths.

Iranian Religions During the Seleucid and Parthian Era

After Alexander the Great’s conquest of Iran, his successors, the Seleucids, attempted to impose Greek culture and beliefs, but the Iranian people largely resisted these influences, choosing instead to preserve their ancient religions and traditions.

Key points about this period include:

- Cultural Resistance:

- Despite the Seleucid efforts to promote Greek culture, the influence on Iranian society was limited, primarily affecting art and architecture.

- Rise of the Parthians:

- The Parthians capitalized on the decline of the Seleucids, establishing the Parthian Empire around 247 BC. They were originally a tribe from the Eastern Scythians, practicing a primitive religion centered on worshipping natural elements such as the sun, moon, stars, and ancestral spirits.

- Religious Diversity:

- The Parthian era saw the emergence of various Iranian religions and philosophical beliefs, with influences from Indian cults contributing to a rich atmosphere of religious diversity.

- Like the Achaemenids, the Parthian dynasty maintained a policy of religious tolerance, allowing followers of different faiths to coexist.

- Jewish Revival:

- Jews, previously persecuted under the Seleucids, regained their status and were able to practice their faith freely.

- Buddhism’s Influence:

- Buddhism spread throughout the eastern regions of the Parthian Empire, with one Parthian prince notably translating Buddhist texts into Chinese.

- Worship of Mithras:

- The cult of Mithras gained popularity during this period and eventually spread to Rome and Anatolia, where it became an independent religion.

- Lack of Official Religion:

- The Parthian Empire did not endorse an official religion, resulting in the limited influence of Zoroastrian Magi at the royal court. This led to tensions between the Magi and the Parthian royalty, causing the former to become somewhat isolated.

- Zoroastrianism’s Resurgence:

- Midway through the Parthian period, some kings converted to Zoroastrianism. Vologases I of Parthia commissioned the collection of Avesta texts and featuring braziers on royal coins as symbols of the faith.

This era reflects a complex interplay of cultural and religious dynamics, showcasing the resilience of Iranian traditions amidst external influences.

Iranian Religions During the Sassanid Era

The Sasanian dynasty marked a significant turning point for Zoroastrianism, intertwining religion and politics in a way that shaped the empire’s governance and cultural identity. Key aspects of this period include:

- Religious Rule:

- The Sasanian rulers practiced religious governance, in which kings and priests supported each other. The political authority of the king was reinforced by religious legitimacy from the Zoroastrian clergy.

- Role of the Mobad:

- The Mobad, or high priest, held the most important religious position. He advised the king on state matters. Lower-ranking priests managed fire temples, conducted legal proceedings, and provided religious education.

- Religious Tolerance:

- Initially, followers of other religions enjoyed the freedom to practice their faith. During Shapur I’s reign, the prophet Mani founded Manichaeism, which Shapur tolerated despite maintaining his Zoroastrian beliefs.

- Increasing Intolerance:

- As Zoroastrian priests gained influence, they began to persecute adherents of other religions, particularly Manichaeans and Christians. This culminated in the arrest and execution of Mani during Bahram I’s reign, leading to widespread persecution of his followers.

- Mazdak’s Reforms:

- Mazdak attempted to reform the social and political landscape, advocating communal ownership and social justice. However, he, too, faced execution, highlighting the intolerance toward alternative ideologies.

- Architectural Legacy:

- The Sasanian era saw the construction of many fire temples, which were significant for Zoroastrian worship. Notable examples include the fire temples of Adur Burzen-Mihr in Khorasan and Azargoshnasp in Azerbaijan, which remain important relics of this period.

Overall, the Sasanian dynasty solidified Zoroastrianism as a state religion, leading to both cultural flourishing and significant religious persecution.

Iranian Religions After the Muslim Conquest of Persia

The rise of Islam marked a transformative period in the history of Persia, concluding the era of the Sassanid dynasty and Zoroastrianism’s dominance. Key points about this transition include:

- Prophet Muhammad’s Mission:

- Prophet Muhammad received a revelation from Allah, taking on the role of the prophet of Islam. He began preaching the message of monotheism secretly for three years in Mecca before publicly proclaiming his teachings.

- Islamic Conquests:

- After Muhammad’s death, his successors, known as caliphs, initiated military campaigns to expand the Islamic state. The Arab army, equipped with relatively primitive military technology, quickly conquered neighboring territories.

- Conquest of Persia:

- Persia was among the first regions to fall to the Islamic army, leading to the defeat of Sassanid generals and the collapse of the Sassanid dynasty. This marked the end of Zoroastrianism’s authority in Iran.

- Decline of Zoroastrianism:

- With the Arab conquest, fire temples were extinguished, and Zoroastrian priests lost their power and influence. The new rulers sought to establish Islam as the dominant faith in the region.

- Gradual Spread of Islam:

- The spread of Islam in Iran occurred over several centuries. Factors contributing to the acceptance of Islam included the desire to avoid heavy taxes imposed by the Caliphate and social, political, and economic motivations.

This period represents a significant cultural and religious shift in Iranian history, leading to the gradual integration of Islamic practices and beliefs into Persian society, which would profoundly influence the region’s identity and governance in subsequent centuries.

After the invasion of Arabs, Iranian Zoroastrians were divided into three groups:

- Those who converted to Islam

- Those who refused to convert to Islam and had to migrate to India

- Those who remained in their homeland and practiced their religion, and had to pay an additional tax called “Jizya”

Later, the tyranny of the caliphate rulers led to uprisings in Iran. One of the people who rose to power by promoting anti-Arab beliefs was Babak Khorramdin. Babak’s followers were followers of Mazdakism.

Iranian Religions After the Caliphate Rule

“They came and tore down and burned everything and killed and took and left.” In these few words, Shams al-Din Juvayni has described what the Mongols did in their invasion of Iran. The extent of Mongol brutality was so severe that some Iranians chose silence for decades. From this period, Sufism and reclusion became common.

The Mongol invasion of Iran brought significant changes to the region’s religious landscape, characterized by a blend of tolerance and eventual conversion to Islam. Key points regarding this period include:

- Mongol Religion and Tolerance:

- The Mongols initially practiced shamanism and were generally tolerant of the religions of the peoples they conquered. Their primary focus was territorial expansion and governance rather than religious conversion.

- Diverse Religious Practices:

- Genghis Khan adhered to traditional shamanic rituals throughout his life. His successors did not follow a single religion; they appointed advisors from various faiths, including Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism, depending on their preferences. For instance, Hulagu Khan converted to Buddhism, while Ahmed Tekuder embraced Islam and supported Muslim communities.

- Religious Dynamics in Iran:

- The Mongol rulers’ fluctuating religious affiliations led to periods of oppression and support for different faiths. Buddhism and Christianity gained followers during this time, reflecting the diverse religious environment under Mongol rule.

- Governance Challenges:

- As the Mongols ceased their destructive invasions, they faced governance challenges and economic difficulties. Recognizing the need for stability and support from the local population, Ghazan Khan of the Ilkhanid dynasty converted to Islam, aiming to strengthen his authority among Iranians.

- Ghazan Khan’s Approach:

- Ghazan Khan expressed a pragmatic view on governance, emphasizing the importance of treating subjects fairly to maintain loyalty and stability. His conversion to Islam marked a turning point for the Ilkhanate, leading to the integration of Islamic practices into governance.

- Shift to Islam and Shia Influence:

- Following Ghazan Khan’s conversion, the Ilkhanate increasingly adopted Islam, with Shia advisors entering the court. Sultan Oljaitu, also known as Mohammad-e Khodabande, became a Shia, further solidifying the Shia identity within the ruling elite.

- Timurid Era Developments:

- During the Timurid period, the influence of Shia Islam continued to grow, with coins minted in the names of Shia imams, reflecting the deepening connection between the state and the Shia faith.

Overall, the Mongol era in Iran illustrates a complex interplay of religious tolerance, strategic conversion, and the eventual establishment of Islam, particularly Shia Islam, as a central element of governance and cultural identity in the region.

Shia Islam, The Official Safavid Religion

The Safavid dynasty, emerging from the lineage of Sheikh Safi-ad-din Ardabili, played a pivotal role in shaping Iran’s religious and political landscape. Here are the key points regarding the Safavid period:

- Establishment of Shia Islam:

- After a prolonged period of power struggles, the Safavids declared Shia Islam, specifically the Jafari branch, the official religion of Iran. This marked a significant shift, as most Iranians were previously Sunnis.

- Enforcement of Shia Practices:

- The Safavid rulers were adamant about enforcing Shia Islam among the population. Resistance to conversion was often met with violence from the Qizilbash army, who were loyal to the Safavid cause.

- Role of the Mujtahid:

- The Safavid kings recognized the Mujtahid (a religious scholar and authority) as the representative of the twelfth Shia Imam, granting them significant power over the lives and property of the people.

- Influence of Clergy:

- Islamic clergymen gained considerable influence during the Safavid period, with their approval required for royal decrees and state affairs. Under Shah Abbas I, clergymen reviewed and authorized royal decrees before they were announced.

- Religious Education:

- The era saw a rise in religious education, leading to the establishment of many religious schools, which helped propagate Shia beliefs and practices.

- Treatment of Religious Minorities:

- Zoroastrians faced discrimination and were forced to pay the jizya, a tax levied on non-Muslims. They also encountered higher taxes on their business activities compared to Muslim businesses.

- Jews and Zoroastrians were generally not treated fairly, as their status was viewed unfavorably in Islamic texts. In contrast, Christians were relatively favored, as the Quran emphasizes coexistence with them. This led to an influx of Christians into Iran during Shah Abbas I’s reign.

- Religious Tolerance and Discrimination:

- While the Safavid regime promoted Shia Islam, it simultaneously marginalized other religious groups, reflecting a complex approach to governance that sought to unify the population under a single religious identity while also accommodating certain groups.

Overall, the Safavid dynasty was instrumental in establishing Shia Islam as a central element of Iranian identity, shaping the political and social dynamics of the region while also instituting policies that affected the treatment of various religious minorities.

Iranian Religions Since the Afsharid Era

The complex interplay of politics and religion in Iran during the rule of Nader Shah and subsequent dynasties highlights the treatment of various religious communities and the evolution of social norms. Below is a summarized version, organized into key categories for clarity.

Nader Shah’s Reign

- Political and Religious Context:

- Inherited a kingdom blending politics and religion.

- Attempted to win support by respecting Shia Islam, particularly the shrine of Imam Reza.

- Aimed to diminish the Shia clergy’s influence to strengthen ties with Sunni Ottomans.

Afsharid Period

- Kashan’s Transformation:

- Became known as a small Jerusalem for Jewish Iranians and Rabbis.

- Thrived economically through trade during Nader Shah’s rule.

Zand Dynasty

- Karim Khan’s Policies:

- Offered greater freedoms to non-Muslims.

- Respected all religions while keeping Muslim clergy out of politics.

Qajar Dynasty

- Societal Values:

- Iranian society upheld Islamic teachings in family values, business ethics, and social norms.

- Increased focus on commemorating Imam Hossein’s martyrdom.

- Construction of “Tekyeh Dowlat” under Naser al-Din Shah Qajar as a significant monument.

- Superstitions and Rituals:

- Rise of superstitious beliefs during commemoration rituals for Imam Hossein.

- Practices like burning bodies with candles and using locks contradicted health care teachings, discussed by Jafar Tehrani in “Tehran-e Ghadim or old Tehran.”

- Treatment of Religious Minorities:

- Zoroastrians and Christians experienced relative freedom.

- Jews faced discrimination, including heavy taxation and lack of dignity.

Iranian Religions in the Modern Era

The lasting influence of religion on various facets of Iranian life, highlighting its profound impact on social beliefs, government systems, and daily routines. Here’s a concise summary:

Influence of Religion in Iran

- Historical Significance:

Religion has always been crucial in shaping Iranian society and governance throughout history.

- Everyday Observations:

Engaging with people in Iran reveals the pervasive influence of religious beliefs on conversations and routines.

Frequently Asked Questions About Iranian Religions

To find answers to your other questions, you can contact us through the comments section of this post. We will answer your questions as soon as possible.

What were the most common ancient Iranian religions?

Ancient Iranian gods were based on natural elements and deities like Zurvan, Mithra, Anahita, and minor deities until the emergence of Zoroastrianism.

What is the relationship between Iranian religions and the identity of the Iranian people?

Religion, whether before Islam or after the arrival of Islam in Iran, has always been part of Iranian identity and a unifying element for Iranians. In ancient Iran, people held special religious ceremonies on the most important occasions in their lives, such as birth, marriage, and death. Military leaders also implemented their religious beliefs on the battlefield. Some traditional Iranian festivals are rooted in ancient Iranian religions, such as Nowruz and Mehregan.

What religion was Iran before Islam?

Persian religions in ancient times were mostly focused on praising natural elements and time. After Zoroaster, most Iranian religions promoted divine and mystical concepts.

What religion are Iranians practicing today?

The main religion of Iranian is Shia Islam, with a Sunni minority, and a small population of Christians and Zoroastrians. There are smaller communities of Druze and Bahai in the country as well.