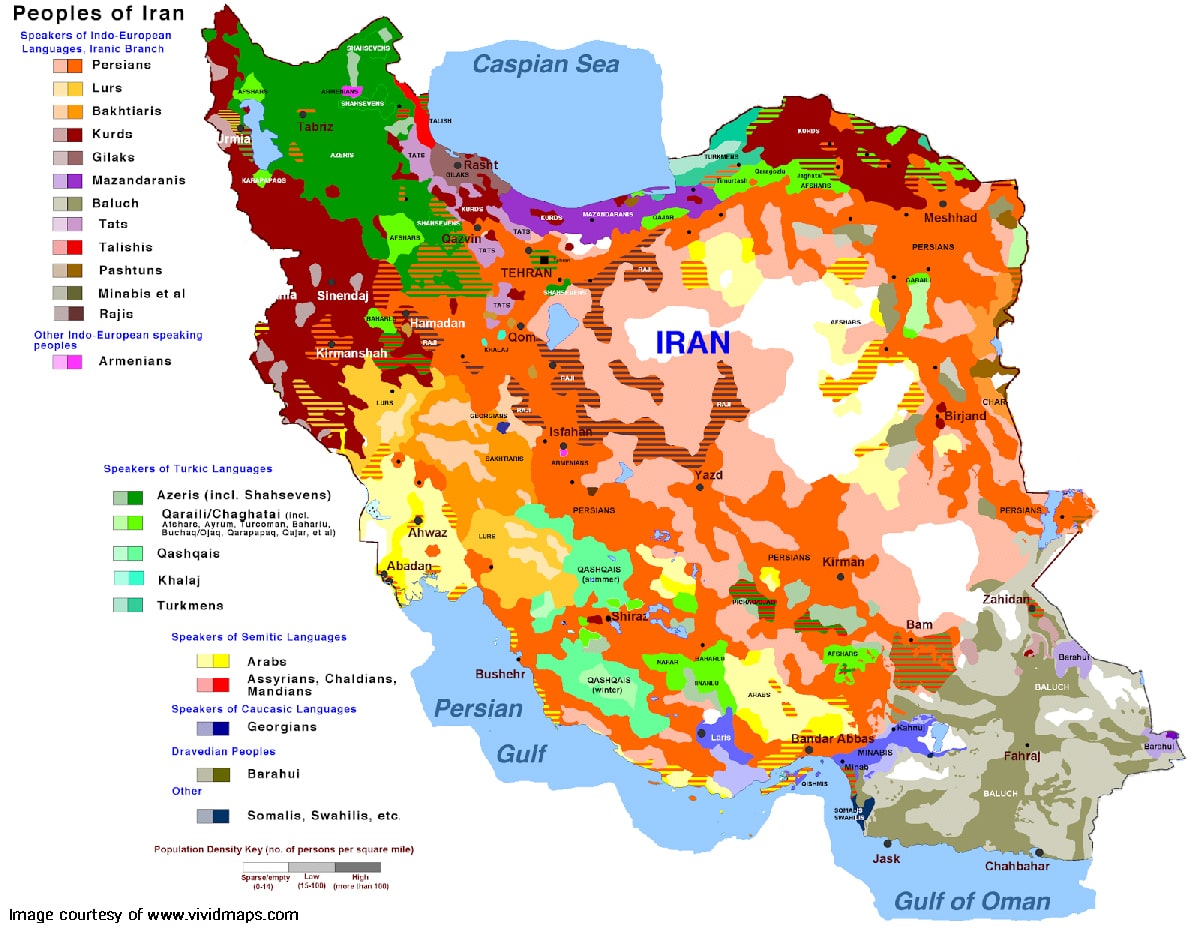

Iran is situated on a high-altitude plateau surrounded by connected ranges of mountains. The well-known deserts of Iran are in two major regions:

1) Dasht-e-Kavir, and

2) Kavir-e-Lut.

They are both some of the aridest and maybe the hottest areas of their kind in the world. A lot of people in the world think of Iran as a country covered by deserts, but this isn’t true. Only parts of Iran are as such. Here you will learn about this natural phenomenon in more detail.

The Desert Pits of Iran

Many who have read about the deserts of Iran have definitely come across Kavir-e-Lut name. Kavir-e-Lut is the largest pit inside the Iranian plateau and probably one of the largest ones in the world. Kavir-e-Lut is a pit formed by broken layers of the earth.

The maximum annual rainfall is approximately 100 mm there. The average altitude of this desert is almost 600 m above sea level (ASL) and the lowest point near “khabis” is almost 300m ASL. In Kavir-e-Lut, a large amount of sand is always moving southward forming sand hills and running sand masses.

Dasht-e-Kavir is a geological pit almost north of Kavir-e-Lut. The minimum altitude of this desert is 400 m ASL. The major part of Dasht-e-Kavir is covered by sand and pebbles and exposed to strong winds and storms that set salt-combined sand in motion like sea waves. At times, this phenomenon forms long sandhills of 40m high.

From the structural point of view, Dasht-e-Kavir is very much different from Kavir-e-Lut. The difference in temperature between days and nights during a year in Dasht-e-Kavir is between 0 and 70 degrees C.

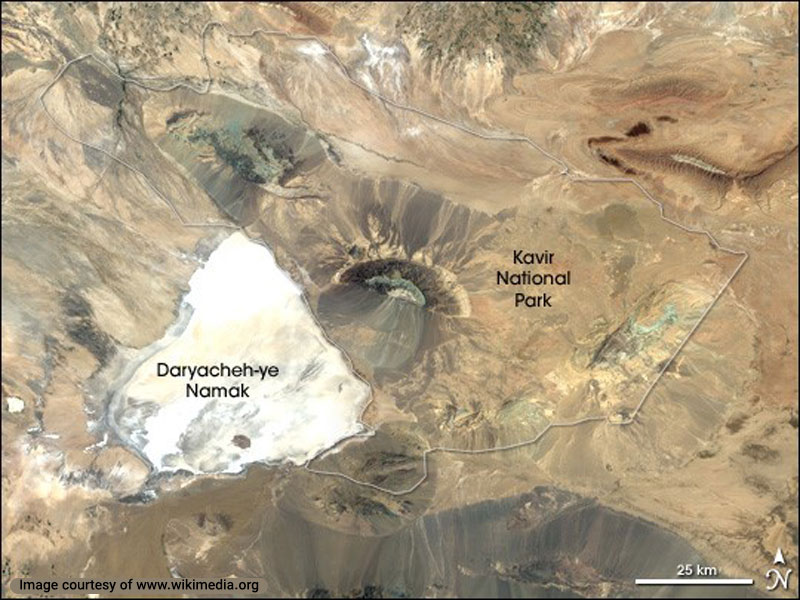

Dasht-e Kavir

Dasht-e Kavir, also known as the Great Salt Desert, is one of the largest deserts in Iran, covering approximately 77,600 square kilometers (30,000 square miles). Located in the middle of the Iranian Plateau, it stretches from the Alborz mountain range in the northwest to the Dasht-e Lut in the southeast.

Geography and Climate

Dasht-e Kavir has an arid climate and extreme temperature variations ranging from scorching daytime highs to freezing nighttime landscape is dominated by vast salt marshes, seasonal lakes, and dunes. The high temperatures and low humidity cause significant evaporation, leaving behind large salt crusts.

Unique Features

Dasht-e Kavir is home to the Kavir Bozorg (Great Kavir) salt marsh, which spans about 320 kilometers (200 miles) in length and 160 kilometers (99 miles) in width. The western part of the desert features the Daryacheh-e Namak (Salt Lake), a protected ecological zone within the Kavir National Park.

Historical Significance

Historically, the desert has been a challenging environment for human habitation due to its harsh conditions. However, it has also been a site for mineral extraction, particularly salt, and has played a role in Iran’s space exploration efforts with the presence of space launch facilities.

Conservation Efforts

Efforts to preserve the unique ecosystem of Dasht-e Kavir include the establishment of the Kavir National Park, which aims to protect the desert’s natural beauty and biodiversity.

Kavir National Park

Kavir National Park, often referred to as “Little Africa,” is a vast and protected area located in the central desert region of Iran. Covering approximately 4,000 square kilometers (1,500 square miles), it encompasses parts of the Dasht-e Kavir, also known as the Great Salt Desert. This national park is one of Iran’s most significant natural reserves, showcasing a rich diversity of flora and fauna amidst its arid landscape.

Geography and Climate

The park is characterized by its rugged terrain, which includes salt flats, dunes, and rocky outcrops. The climate is arid, with extreme temperature variations between day and night. Summers are scorching hot, while winters can be surprisingly cold. The park’s unique geological features include seasonal salt lakes and marshes, which create a dynamic and ever-changing environment.

Unique Features

Kavir National Park is home to a variety of unique ecosystems and wildlife. It boasts a range of habitats, from vast deserts to lush oases, providing sanctuary to numerous species of plants and animals. Notable wildlife includes the Persian onager (a type of wild ass), Asiatic cheetahs, Persian leopards, and various bird species such as bustards and flamingos. The park is also known for its impressive salt domes and intriguing geological formations.

Historical Significance

The region has a rich history dating back to ancient times. It has been a site for caravan routes and trade, connecting different parts of Persia. The ancient Qanats (underground irrigation systems) in and around the park reflect the ingenuity of early inhabitants in harnessing water resources in such a harsh environment.

Conservation Efforts

Kavir National Park is dedicated to the conservation of its unique biodiversity and natural beauty. Efforts include strict regulations to protect endangered species, habitat restoration projects, and the promotion of sustainable tourism. The park also serves as a research area for scientists studying desert ecology and conservation practices.

Namak Lake

Namak Lake, also known as Daryacheh-ye Namak, is a significant salt lake located in the heart of Iran. It spans an area of approximately 1,800 square kilometers (700 square miles) and is situated in the Qom and Arak regions. This lake is a striking feature of the central Iranian landscape, often reflecting the intense sunlight off its vast, shimmering salt flats.

Geography and Climate

Namak Lake lies in a basin surrounded by arid plains and low hills. The climate in this region is harsh and dry, characterized by high temperatures during the summer and cold winters. The lakebed is primarily composed of salt and mineral deposits, which create a white, crusty surface that can be seen for miles.

Unique Features

Namak Lake is known for its seasonal changes; during the wet season, it transforms into a shallow, saline lake, while in the dry season, the water evaporates, leaving behind thick salt crusts. These salt formations are not only fascinating to look at but also play a crucial role in the local economy through salt extraction.

Historical Significance

The lake has historical and cultural importance, with ancient trade routes passing by its shores. Traders used the salt from Namak Lake for preservation and seasoning, making it a valuable commodity in ancient times.

Conservation Efforts

Efforts to preserve Namak Lake and its surrounding environment focus on mitigating the impacts of industrial activities and ensuring sustainable salt extraction practices. The lake and its ecosystem are vital for local wildlife, providing a habitat for various bird species, especially during migration periods.

Sargardan Island

Sargardan Island, also known as the Wandering Island, is a unique and intriguing landmark located in the middle of Namak Lake in Iran. This island is named for its peculiar movement, as it appears to shift locations within the salt lake due to water levels and wind patterns.

Geography and Climate

Sargardan Island is characterized by its rugged terrain and salt-encrusted surface. The climate in this region is arid, with extremely high temperatures in the summer and colder temperatures during the winter months. The island’s position within the saline environment of Namak Lake means that it is surrounded by a landscape of salt flats and seasonal shallow waters.

Unique Features

The most fascinating aspect of Sargardan Island is its perceived movement. As water levels in Namak Lake fluctuate, the island appears to “wander” across the lake. This phenomenon is primarily due to the shifting salt crusts and changing water depths. Visitors to the island can witness these changes over time, making it a dynamic and ever-changing natural feature.

Historical Significance

Sargardan Island holds cultural and historical importance for the local communities. It has been a site of interest for explorers and geologists studying the unique environmental conditions and geological formations of the salt lake.

Conservation Efforts

Efforts to preserve Sargardan Island focus on maintaining the ecological balance of Namak Lake and protecting the island’s unique characteristics. Conservation initiatives aim to mitigate the impact of human activities and ensure the sustainable use of the lake’s resources.

Maranjab Desert

The Maranjab Desert, located in the Isfahan Province near the city of Kashan, is one of Iran’s most captivating desert landscapes. This desert is renowned for its striking beauty, diverse terrain, and rich cultural history, making it a popular destination for adventurers and tourists alike.

Geography and Climate

The Maranjab Desert spans a vast area with a diverse topography that includes towering sand dunes, salt plains, and desert oases. The climate is typically arid, with scorching hot summers and cold winters. The desert’s location near the Dasht-e Kavir, also known as the Great Salt Desert, adds to its dramatic landscape.

Unique Features

One of the most notable features of the Maranjab Desert is its high dunes, some of which reach heights of up to 70 meters (230 feet). The desert is also home to the stunning Maranjab Caravanserai, a historical rest stop built in the 16th century during the Safavid era. This caravanserai provided shelter and supplies to travelers along the Silk Road and remains a significant cultural landmark today.

Historical Significance

The Maranjab Desert holds historical significance due to its strategic location along ancient trade routes. The Maranjab Caravanserai served as a crucial hub for merchants and travelers, facilitating trade and cultural exchange between Persia and neighboring regions. The remains of ancient pathways and trade routes can still be traced across the desert.

Conservation Efforts

Efforts to preserve the natural beauty and cultural heritage of the Maranjab Desert include sustainable tourism practices and the protection of historical sites like the Maranjab Caravanserai. Initiatives focus on minimizing the environmental impact of tourism and ensuring the desert remains a pristine and accessible destination for future generations.

Rig-e Jenn

Rig-e Jenn (Dune of the Jinn) is an infamous desert region in Dasht-e Kavir. It is regarded as one of the most dangerous deserts in the world, and for hundreds of years, people believed the Jinn inhabited it. People often avoided this desert in fear of malevolent supernatural entities and considered it a cursed land.

There are no traces of civilization in this region in the past, and no mentions of any cities or villages in historical documents. Rig-e Jenn is truly deserted, which further promotes the notion that this land is inhibited by evil spirits.

Mystery of the Jinn

Jinn are mythical creatures from Arabic cultures that predate Islam but are mentioned in the Quran. Jinn means hidden from sight, as these supernatural creatures can supposedly turn invisible. The Jinn can also shapeshift, appearing to desert travelers as animals or humans.

Even today, some people still believe the area is inhabited by the Jinn, and warn anyone against crossing through this desert. In the past, people who went to the desert and never returned were considered victims of the Jinn.

There are no drinkable water sources such as wells or springs in Rig-e Jenn. Therefore, some believe the reports of Jinn’s sightings in Rig-e Jenn are a result of dehydration-caused hallucinations. This scarcity of water is the main reason for the long-lasting stigma of crossing this desert in the past.

Geography of Rig-e Jenn

This desert region is approximately 3800 km2 and is covered with dunes and salt marshes. The entire area used to be part of the Tethys Ocean in the prehistoric period. This is the reason for the excessive presence of salt on the surface of the desert.

This dune desert is located on the southwest and west of Dasht-e Kavir. To the south, this desert is limited by the Molahadi Mountain. The Namak Lake and Kavir National Park are located to the east of the desert region. It is one of the oldest and largest protected nature reserves in Iran.

The largest section of this desert is in Semnan Province but it stretches to Isfahan Province to the southwest and South Khorasan Province to the southeast. A small part of this desert is located in the Razavi Khorasan province in the east.

There are several rivers in this area including Habaleh Rud in the northeast section of the desert. The Vargi and Rameh rivers in the north and Khushab Rud are other rivers in this region. All these rivers are saltwater and cannot be used for drinking. The 6-7 km salt layer in this desert renders all perspiration into saltwater as well. There are a handful of small springs in Rig-e Jenn but they have very low flows of saltwater as well.

Wildlife and Plant Life in Rig-e Jenn

Most of this scorching desert is uninhabited by any animal or plant. But there are small areas with vegetation that harbor unique species that have adapted to thrive in the desert. Gowd-e Do Bagh (Two Garden Pit) in the heart of Rig-e Jenn is one of these reserves. There are a variety of plants and animals in this ecosystem. The area is under the protection of Iran’s Department of Environment. It is recommended to avoid these protected areas to protect the natural balance of the ecosystem.

There are Tamarisk trees, Haloxylon shrubs, and Calligonum in the area. Sighting of endangered animals such as wolf, jackal, the Rüppell’s fox and the Sand Cat (Felis margarita), Caracal, rabbit, Meriones, Jaculus, and Pikas. There are also several species of snakes, scorpions, and lizards such as Agamas and Geko. Avian wildlife is limited to the common buzzards and the Golden Eagle.

During the reign of Shah Abbas I, there were reports of Goitered gazelle in the area which were hunted to extinction. In addition, the neighboring Kavir National Park is home to the Asiatic Cheetah which have been sighted in this desert.

Several areas in the Rig-e Jenn desert are no-hunting zones including the Molahadi no-hunting zone, Abbad Abad Nain protected reserve, Ardestnan no-hunting zone, Choopanan no-hunting zone, and especially Kavir National Park.

History of Rig-e Jenn

There are no records of passage through this desert from the 1900s. Most Iranians in the past considered this area highly dangerous, and some still hold this belief. The first recorded crossing is marked in Sven Hedin’s travelog “Iran in the Nasserid Era”. This Swedish traveler and his companions crossed the west and southern areas of the Rig-e Jenn but did not pass directly through the desert.

The second person to launch an expedition into the desert was Alfons Gabriel, an Austrian travel writer. He attempted to cross the desert but had to turn back towards Yazd because of the desert’s extreme conditions.

The first successful voyage in Rig-e Jenn was carried out by Mansur Atarodi in 1997. He was the deputy chief of the natural resources office in the Iranian Department of Environment. Along with the head of Kavir National Park and an envoy of pickup trucks and off-road vehicles, they successfully crossed the desert. Atarodi and his team crossed the desert again a year later, paving the way for new travelers to cross this region. They broke the stigma surrounding the desert and its cursed status.

How to Travel to Rig-e Jenn

Despite the supernatural myths surrounding this destination, it is one of the most beautiful and scenic deserts in Iran. However, it is still extremely dangerous to cross this desert without proper guidance and equipment. The salt marshes in the region can easily trap and bury any unsuspecting travelers. That is why this area is also known as the Bermuda Triangle of Iran.

The high temperature, stark contrast between day and night temperatures, and lack of water sources call for expert preparation. You should pack the necessary food and water, sunscreen and sunglasses, sun hats, comfortable shoes, and loose cotton clothing. It is very dangerous to attempt to cross this desert without an expert guide and the company of a group tour.

The Ecological Conditions of Iran Deserts

Some of the ecological features of the deserts in Iran are strong sunshine, relatively little humidity, little rainfall, and excessive vaporization. Depending on how far a point is from higher altitudes, the temperature is varied.

A point far from altitudes can reach up to 60 degrees C during summer. The average temperature during January and May is 22 degrees C and 40 degrees C respectively. In general, the ecological conditions of the deserts in Iran are so severe that they are not tolerable either in summer or winter.

It rarely snows there. The annual relative humidity is below %30. During summer, it decreases, at times, down to %0. It usually rains during winter and sometimes showers lead to washing away the earth. It goes without saying that there cannot be proper enough soil and water for plants to grow. Since these regions are always open to winds and there are not sufficient plants to preserve soil, wind erodes the earth and brings about losses. Therefore, blocking winds with wood-made walls and planting shrubs and trees are carried out to confront the destructive natural forces.

Living Conditions in Deserts of Iran

It is always water that determines living conditions everywhere. Again it is just water that helps plants grow and people stay in an area within the desert. Water is not easily accessible at every corner of the deserts of Iran.

Life goes on in the areas where water can be found in springs or through the ancient technique of making underground aqueducts called kariz (qanat). At times, semi-deep wells are dug to get water. So, desert dwellers make the most of the minimum water they get. Local people use highly tolerant animals, camels, to travel through the desert. Usually, vines or similar trees with deep-going roots are planted so that they could survive.

Making a Living in the Deserts

People live only in oases on small scales and they rely on farming, herding animals, and migrating. They have to plant wheat, barley, fruit trees, and alike. In some areas, farming is also in vain. So, they have to make a living just by herding cattle. When neither of the above helps, they have to migrate somewhere else in search of better living conditions.

Accommodation & Clothing

Sun-dried brick, raw mud, and in some areas a limited quantity of stone are the only constructional materials used to build houses. Walls have to be built very thick for the sake of insulation and roofs have to be built in cupola or vaulted forms to last longer.

People are usually dressed in bright colors and clothing is mostly made of cotton. They are loose and long unless people are influenced by the city dwellers’ culture.

Although the Iranian plateau forces its compelling situations, its inhabitants struggle for preserving living conditions. These hard-working people, who have been struggling for thousands of years in the deserts of Iran, will not give up so easily.

I’ve noticed large circular berms in the desert north east of Qom. What are these for.

Thanks I love Iran.

Hi Tj. I need to see what you’re talking about. Can you send me a photo so that I can see it too?