Iranian architecture has a long and intricate history. From historical landmarks like Chogha Zanbil, Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, and Taq Kasra to the National Museum of Iran. So the scope of this article is limited to historical highlights of the evolution of Iranian architecture.

Pre-Islamic Architecture

The architecture of pre-Islamic Iran is part of our intangible cultural heritage and historical legacy of the nation before the Arab Invasion of Persia. This era showcases an incredible diversity of architectural styles of Elamite, Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sassanid civilizations, each leaving an indelible mark on Iran’s architectural heritage. These elements reflect the sociopolitical and religious dynamics of their times and the cultural exchange between ancient Iran and other civilizations such as Mesopotamia, the Ancient Greeks, and Romans.

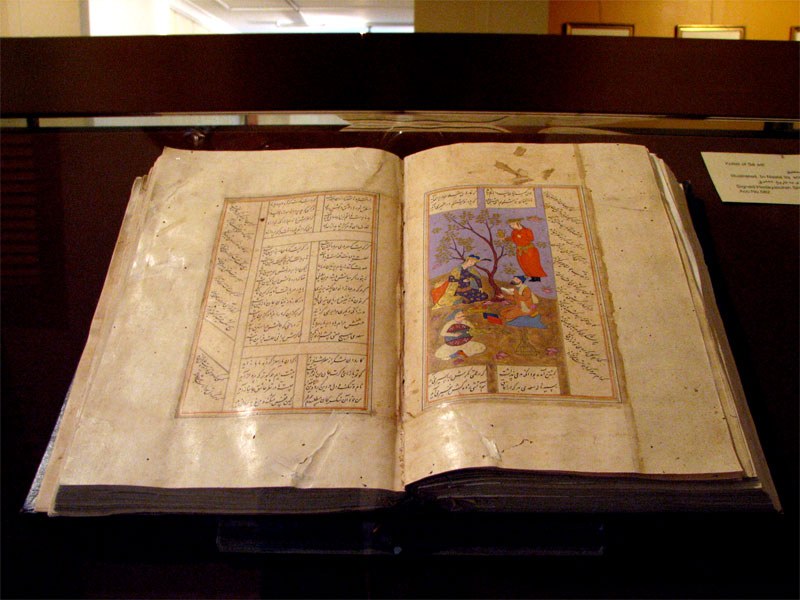

Elamite Architecture

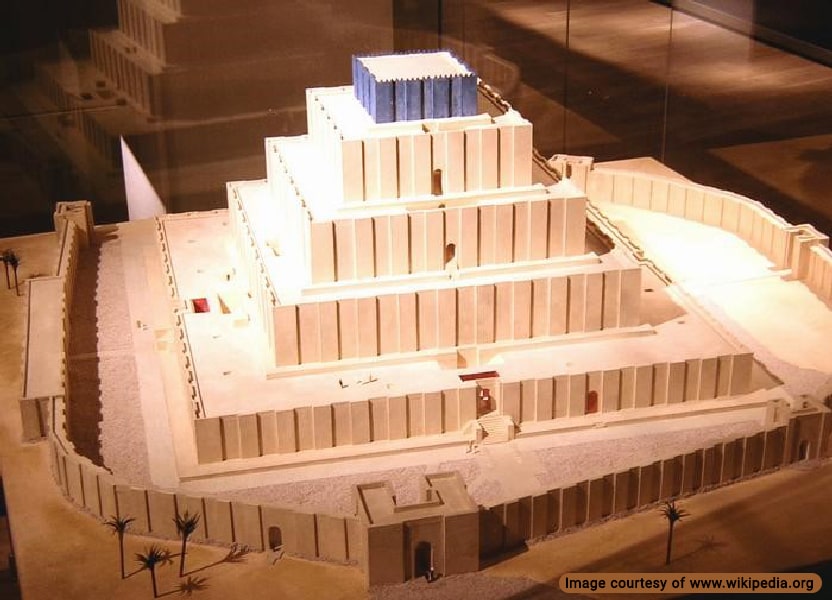

One of the best-preserved examples of Elamite design is the Tchogha Zanbil Ziggurat, dating back to the Elamite period around 1250 BCE, which exemplifies the influence of Mesopotamian construction techniques on Iranian architecture. This stepped Ziggurat made of mud bricks symbolizes the connection between the earthly and the divine.

Features of Elamite Architecture

- A stepped pyramid structure, use of mud bricks

- Symbolizes the connection between the earthly and the divine

- Features multiple terraces and a central sanctuary reflecting religious beliefs

- Construction of water distribution and sewage systems

- Use of glass paste in design

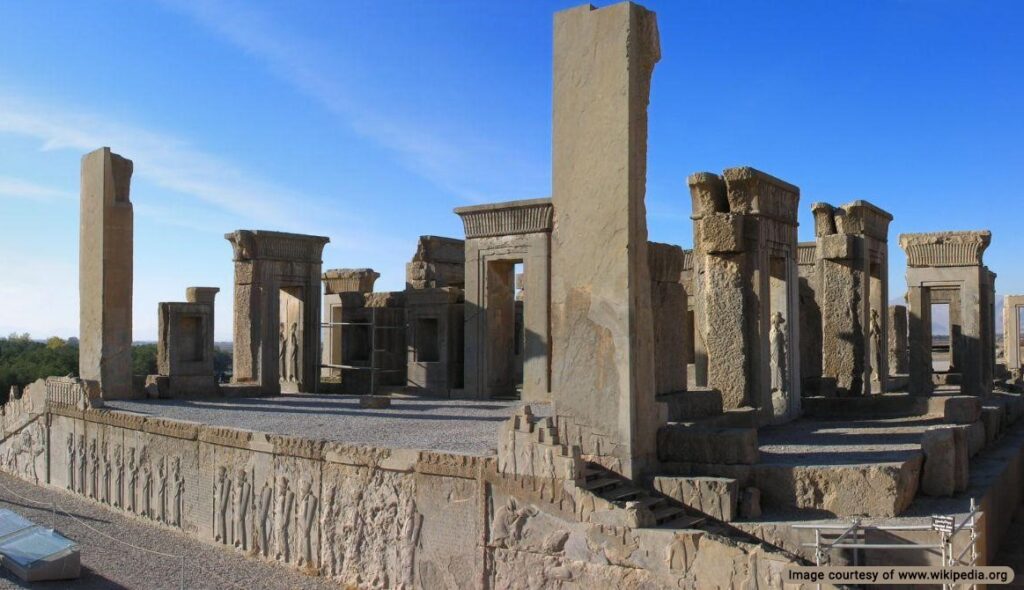

Achaemenid Architecture

A prime example of pre-Islamic architecture is Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. Constructed under the patronage of Darius I in the 6th century BCE, this grand site boasts imposing palaces, colossal columns, and intricate relief sculptures, depicting the power and diversity of the empire. The precision and engineering ingenuity of its design with a main terrace supported by platforms underlines the grandeur of the Achaemenid period. The Apadana Palace, adorned with 72 awe-inspiring columns and exquisitely carved stone reliefs, stands as a testament to the artistic and architectural prowess of the era.

Features of Achaemenid Architecture

- Imposing palaces, colossal columns, and intricate relief sculptures

- Precision and engineering ingenuity with a main terrace supported by platforms (Iwan)

- Awe-inspiring columns and exquisitely carved stone reliefs

- The Persian Garden design (Paradise), a royal enclosure with vegetation

Parthian Architecture

Following the decline of the Achaemenid Empire and the rise of Seleucids, the Parthian Empire innovated dome and arch construction. The remnants of Hatra in modern-day Iraq stand as a testament to a synthesis of Greek and Persian styles, featuring circular temples and military-style fortifications. The adaptation to arid surroundings with the use of indigenous materials and the incorporation of diverse cultural influences showcase the empire’s architectural adaptability.

Features of Parthian Architecture

- Innovations in dome construction and vault creation

- Synthesis of Hellenistic (Greek) and Persian styles, featuring circular temples and robust fortifications

- Adaptation to arid surroundings using Indigenous materials and diverse cultural influences

- Circular cities and the use of Euclidean geometry in urban planning

Sassanid Architecture

During the Sassanid era, Parthian architecture was adopted and imbued with Sassanid sophistication known for grand structures, intricate brickwork, and innovative arches. The Taq Kasra (Arch of Ctesiphon) is a prime example, featuring one of the world’s largest single-span brick arches, demonstrating the engineering and artistic finesse of Sassanid architects. The incorporation of large Iwans (vaulted spaces) and elaborate interior decoration signaled a shift towards more dynamic interior spaces, eventually influencing Islamic architecture in the subsequent centuries.

Features of Sassanid Architecture

- Grand structures, intricate brickwork, and innovative arches

- Construction of one of the largest single-span brick arches

- The incorporation of spacious vaulted areas and elaborate decoration signaled a shift toward dynamic interior design.

In conclusion, the legacy of pre-Islamic architecture in Iran is a fascinating mosaic comprising various influences and innovations that have left an enduring impact on the cultural identity of the region. The magnificence of sites like Persepolis, Tchogha Zanbil, Hatra, Ctesiphon, and Taq Kasra attests to the architectural accomplishments of ancient Persia. It also sheds light on the complexities of the cultures responsible for their development. These structures continue to serve as a source of inspiration and study, laying the groundwork for the architectural advancements that unfolded in the Islamic era and European architecture.

Contemporary Iranian Architecture

Contemporary Iranian architecture reflects a dynamic blend of tradition and modernity. Domestic and foreign architects were tasked to design new buildings. They were inspired by the sociopolitical and cultural changes in the country, drawing inspiration from Iran’s rich architectural history, as well as Islamic and European styles of architecture. Iran’s contemporary architecture can be divided into Qajar, Pahlavi, and Post-Revolution periods.

Qajar Architecture

The impact of the Russo-Persian wars and the defeat of Qajar led to a cultural revolution in Iran, which inspired the Constitutional movement. Its impact on Iranian architecture is evident in Qajar-era buildings. At first, Russian architectural elements are implemented in facade decorations Then, these European design elements are added to interior decoration.

The most notable Qajar buildings include Golestan Palace, Tehran Grand Bazaar, modern schools such as Dar al-Fonun, Agha Bozorg School, Ferdows Garden, and Masoudieh Mansion.

Features of Qajar Architecture

- The amalgamation of Iranian and European styles, design elements, and architectural features

- Wide facades and long rectangular plans

- Use of Orosi (sash) doors and windows

- Implementation of central courtyards and veiled architecture

- Karbandi decorations in vestibules

Pahlavi Architecture

During the Pahlavi period, many foreign architects were commissioned to build new monuments and governmental buildings alongside Iranian designers. Reza Khan’s militarism impacted Pahlavi’s style of architecture. He started several urban expansion projects and the Trans-Iranian railway with the help of European architects and construction contractors. He also kickstarted the construction of several royal palaces in different areas.

This era saw the first examples of modernist urban planning and architecture in Iran, especially in central Tehran where the first streets were constructed. Tehran University is one of the prime examples of modern Pahlavi buildings. Other notable architectural projects in this period include the Azadi Tower, the Veresk Bridge, Saad Abad Palace, the Tomb of Ferdowsi, the Bank Melli building, and Shahrbani Palace.

Features of Pahlavi Architecture

- Emphasis on grandeur and monumental scale

- Integration of traditional Persian architectural elements with modernist influences

- Use of modern construction materials such as concrete and steel

- Influence of international architectural styles such as Art Deco and Modernism

- Construction of monumental public buildings and infrastructure projects

- Emphasis on urban planning and development

- Symbolic use of architecture to express national identity and cultural heritage

Modern Iranian Architecture

Since 1979, architecture in Iran has evolved significantly, mirroring the country’s aspirations, religious values, and the influence of global architectural trends. One of the most significant developments in contemporary Iranian architecture is the emergence of a distinct modern architectural style that integrates elements of traditional Persian and Islamic architecture. This style is characterized by intricate tilework, bold geometric patterns, and symmetric designs. The approach balances modern design principles with traditional aesthetics, resulting in innovative styles that reflect Indigenous identity while participating in global architectural discourses.

After the revolution, housing projects were expanded beyond Tehran and larger cities. The new government established the Ministry of Agriculture Jihad, which focused on expanding water, power, and electricity access to villages all over Iran.

Urban planning focused on the expansion of city limits especially in cities like Tehran, Isfahan, and Mashhad. This led to the construction of new municipal districts, and the development of urban green space projects and cultural centers, all of which led to an increase in urban migration.

After the Iran-Iraq war and the widespread destruction of urban areas, reconstruction efforts focused on Southern Iran. Meanwhile, Iran witnessed a large-scale migration from villages to cities that created an overpopulation problem that the country still faces.

Notable modern Iranian architectural projects include the Milad Tower, Tabiat Bridge, Karun Dams, and the Navvab project.

Features of Modern Iranian Architecture

- Emphasis on Islamic architecture and design elements

- Integration of symbolic elements reflecting the values of the Islamic Revolution

- Incorporation of modern and contemporary architectural styles while adhering to Islamic principles

- Utilization of sustainable and eco-friendly design principles Iran Pavilion

- Influence of Iranian traditional architecture and heritage on contemporary building design

- Development of grand public spaces and monumental structures reflecting national pride and identity

- Promotion of architectural projects that symbolize the ideals of the Islamic revolution

Contemporary Iranian architecture blends tradition and innovation in response to the complexities of modern Iranian society. Architects in Iran are giving increasing attention to sustainability, cultural identity, and community engagement, fostering a new architectural language that connects the historical past with current aspirations. This evolution reflects the challenges and opportunities faced by the nation and highlights the creativity and ingenuity of Iranian architects in designing modern Iran.

UNESCO Designated World Heritage Sites

Iran is home to an impressive number of UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites, showcasing its rich cultural heritage, historical significance, and remarkable architectural achievements. As of October 2023, Iran boasts 27 World Heritage Sites, representing a diverse range of historical periods, architectural styles, and cultural heritage. The first

| Site Name | Province | Year | Historical Period | Notable Features |

| Hegmataneh | Hamedan | 2008 | Ancient/Persian | Tombs, ruins of Medes civilization |

| The historical bazaar of Tabriz | East Azerbaijan | 2010 | Various | Covered market, caravanserais |

| Sheikh Safi al-din Khānegāh and Museum | Ardabil | 2010 | Safavid (16th century) | Imamzadeh, intricate tilework |

| The ancient city of Gohar Shad | Khorasan Razavi | 2015 | Timurid (15th century) | Monumental structures, intricate calligraphy |

| Masjed-e Jameh of Isfahan | Isfahan | 2012 | Islamic (c. 11th century) | Mosaic tile, calligraphy |

| The early Islamic area of Isfahan | Isfahan | 2012 | Islamic (c. 10th century) | Qanat systems, Islamic architecture |

| Takht-e Soleyman | West Azerbaijan | 2003 | Sassanian (c. 3rd century) | Zoroastrian fire temple, inscriptions |

| Golestan Palace | Tehran | 2013 | Qajar (19th century) | Qajar architecture, intricate tile work |

| Jameh Mosque of Isfahan | Isfahan | 2012 | Seljuk (11th century) | Four-iwan style, minarets |

| The Armenian Monastic Ensembles of Iran | East Azerbaijan | 2008 | Medieval (c. 11-13th centuries) | Stone churches, frescoes |

| Hyrcanian forests | Golestan Province | 2019 | Ancient forests | Diverse flora and fauna, ecological features |

| Ancient City of Susa | Khuzestan Province | 2015 | Ancient (c. 4000 BC) | Ziggurat, archaeological remains |

| Persian Gardens | Various Locations | 2011 | Various | Quadripartite layout, water features |

| Shushtar Historical Hydraulic System | Khuzestan Province | 2009 | Ancient (c. 300 BC) | Qantas, dams, canals |

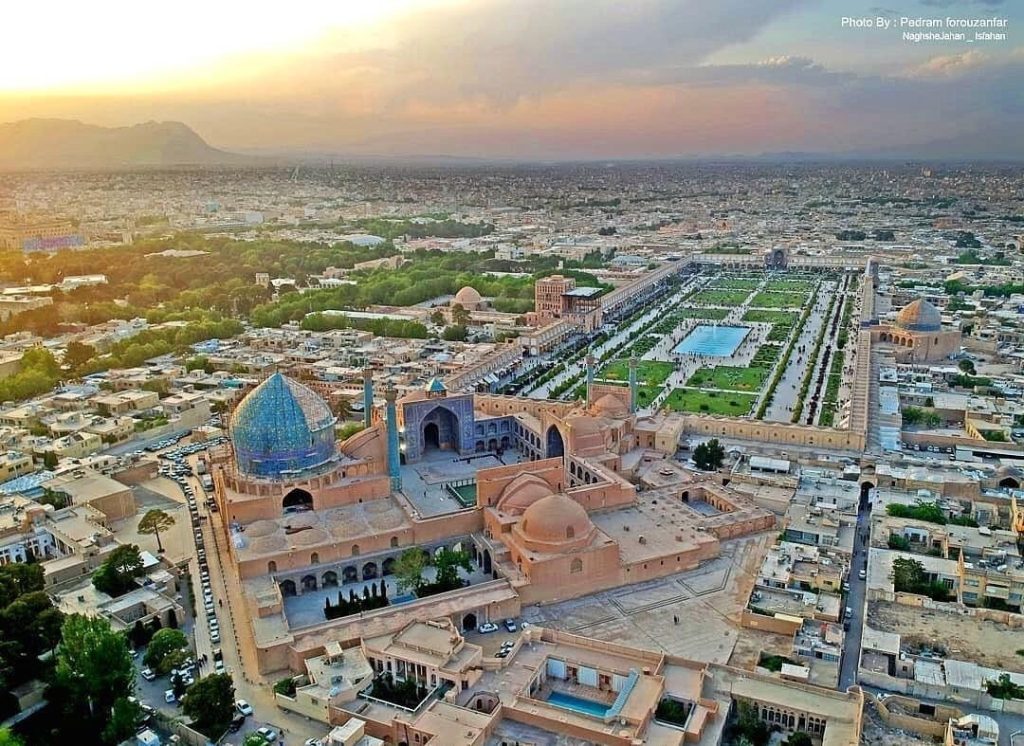

| Naqsh-e Jahan Square | Isfahan | 1979 | Safavid (17th century) | Imam Mosque, Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque |

| historic city of Yazd | Yazd Province | 2017 | Islamic (c. 9th century) | Windcatchers, adobe buildings |

| Bam and its Cultural Landscape | Kerman Province | 2004 | Sassanian (c. 7th century) | Citadel, adobe architecture |

| Tchogha Zanbil | Khuzestan Province | 1979 | Elamite (c. 1250 BC) | Ziggurat structure, mud-brick construction |

| Gonbad-e Qabus | Golestan Province | 2012 | Ziyarid (11th century) | Tall tower, intricate brickwork |

| Persian Gardens | Various Locations | 2011 | Various | Quadripartite layout, water features |

| Takht-e Suleyman | West Azerbaijan | 2003 | Sassanian (c. 3rd century) | Zoroastrian fire temple, inscriptions |

UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites in Iran offer a peek into the country’s rich and diverse cultural heritage. These sites are monuments to Iranian history and cultural identity and showcase human creativity and resilience. They encourage global recognition and appreciation of Iran’s contributions to the world and highlight the significance of preserving and valuing cultural heritage for future generations. Each site tells a timeless story, connecting past achievements with contemporary identity and belonging.

Common Architectural Styles in Iranian Architecture

Over time, the architecture of Iran has changed and adapted to its environment, which has led to the emergence of different architectural styles:

- First Persian Empire Style: Achaemenid era

- Parthia Style: Parthian Empire era

- Second Persian Empire Style: Sassanid era

- Khorasani style: Samanid, Seljuk, and Anushtegin era

- Razi style: Samanid, Seljuk, Anushtegin era

- Azari style: Ilkhanid era

- Isfahani style: Safavid period

Common Structure Types in Iranian Architecture

The following structures have been built in Iran over many centuries. Design elements, decorations, personal preferences, and other features of Iranian architecture are present in these examples:

Iranian Mosques

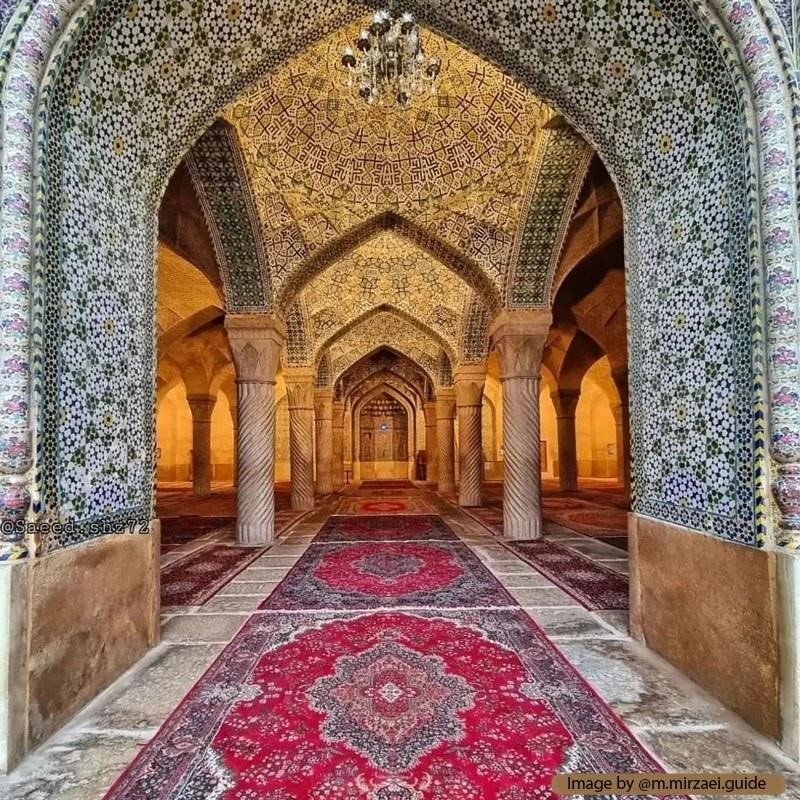

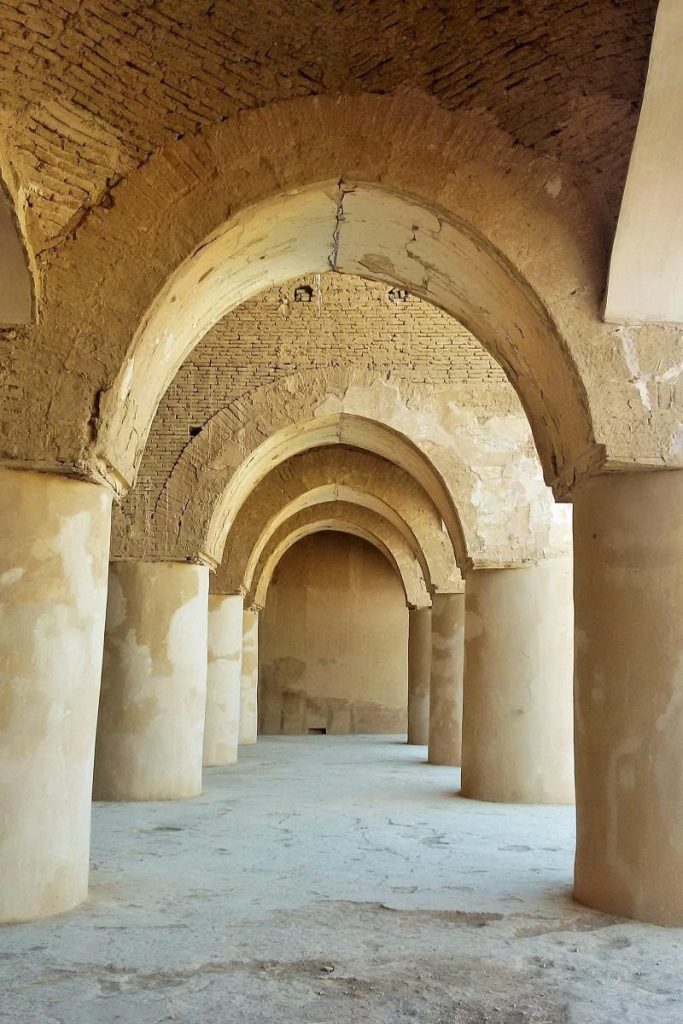

At the beginning of the arrival of Islam in Iran, mosques were built in a very simple style following Sassanid architecture. Khorasan is known as the birthplace of the first examples of Islamic architecture in Iran. In Khorasan and the Khorasan style, the overall design of the buildings is adapted from the mosques of early Islamic periods, and the mosques were built as Shabestan (prayer halls) with many columns.

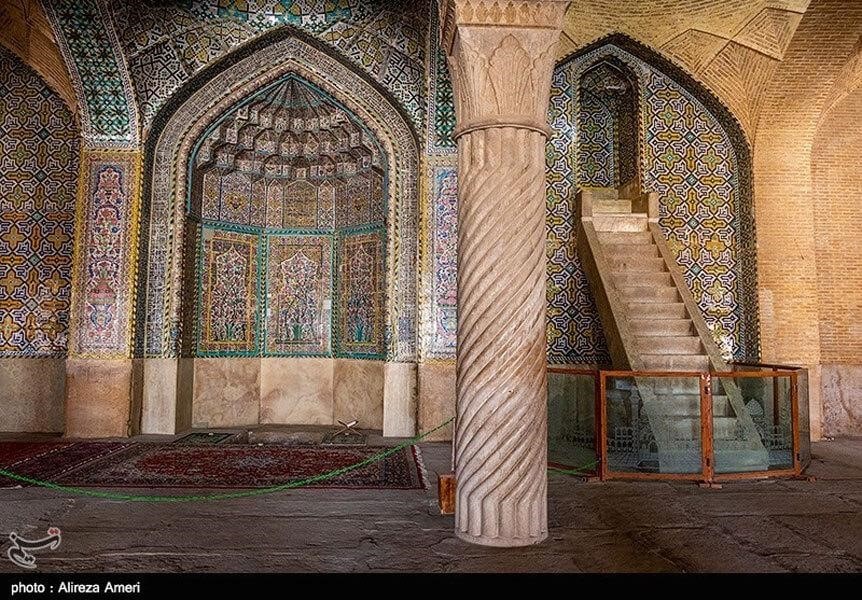

Numerous columns were placed around the central courtyard and formed the Shabestan or Ravagh (Portico). The arches in mosques are often oval or egg-shaped, modeled after Ardashir Papakan Palace or the Firozabad Palace and the Taq Kasra from the Sassanid era. Mihrab (a niche in the wall in the direction of Qibla) and Manbar (pulpit) gradually found a special place in the architecture of Iran mosques and became a place for artists.

Traditional Iranian Hammam (Bathhouse)

Iranians have cared about cleanliness and washing their bodies since ancient times. The word Garm-abeh does not mean hot water; Abe is a suffix that indicates the word refers to a place. Like Goor-abeh, which means a place of burial. Bathhouses were usually built near mosques.

Traditional Iranian bathhouses were built thoughtfully designed to prevent heat loss and had measures that were health-aware. For example, there was a spiral corridor between the Dehliz (vestibule) and the entrance of the bathroom, which prevented heat loss and would prevent a temperature shock, which would happen if a person suddenly went outdoors after a hot bath.

Dehliz (vestibule), Beyneh (changing room), Miandar (a vestibule between Beyneh and Garmkhaneh designed with a turn to prevent heat loss), Garmkhaneh (cleaning and massage area), and Khazaneh (hot water pool) are the main parts of the traditional Garmabah. Hammam Khan in Kashan, Garmabeh Pahneh in Semnan, Vakil Historical Bath in Shiraz, and Ganjali Khan Historical Bathhouse in Kerman are some of the old and famous traditional bathhouses with Iranian architecture.

Iranian Kakh (Palace)

The modern definition of a Kakh or palace is different from its ancient concept. In the past, unique buildings with exceptional architecture were called Kakh. This structure could be a temple, a military stronghold, or a royal residence.

Gradually, the definition of a palace changed and it was only used to refer to a royal residence. Persepolis in the Achaemenid period, Ashur Palace in the Parthian period, and Ctesiphon in the Sassanid era are some of the most famous ancient Persian palaces with Iranian architecture. There are not many palaces left from the early Islamic period. The Qusr(palace) Amra and Qasr Al-Mshatta, which were built during the Umayyad Caliphate were an adaptation of the Sassanid Khak design.

The palaces entered a new phase after the Safavid era. Mesmerizing examples of prominent buildings with Iranian architecture were constructed in the three Safavid capitals, Tabriz, Qazvin, and Isfahan. This process continued during the Afsharid and Qajar period. The Nader Palace or Sun Palace is a remnant of the reign of Nader Shah and Sahebqaraniyeh Palace and Shams Ol-Emareh Palace from the Qajar period are prime examples of the Iranian palace architecture in their period. Since the Safavid era, palaces were decorated with brickwork, plasterwork, Āina-kāri (mirrorwork decoration), and mosaic designs.

Iranian Meydan (Square)

Meydan originates from the word Mian and it means the middle of the city and an open space for people to gather. The squares are divided into two categories:

- Large city squares, which are in the heart of the city, and essential buildings such as the market, school, and bathhouse are built around it.

- Lard squares, which are small and not near the city center. This is where goods were distributed from there, such as Tarehbar Square (farmer’s market) and Sabzeh Meydan (street vendor’s center in Tehran).

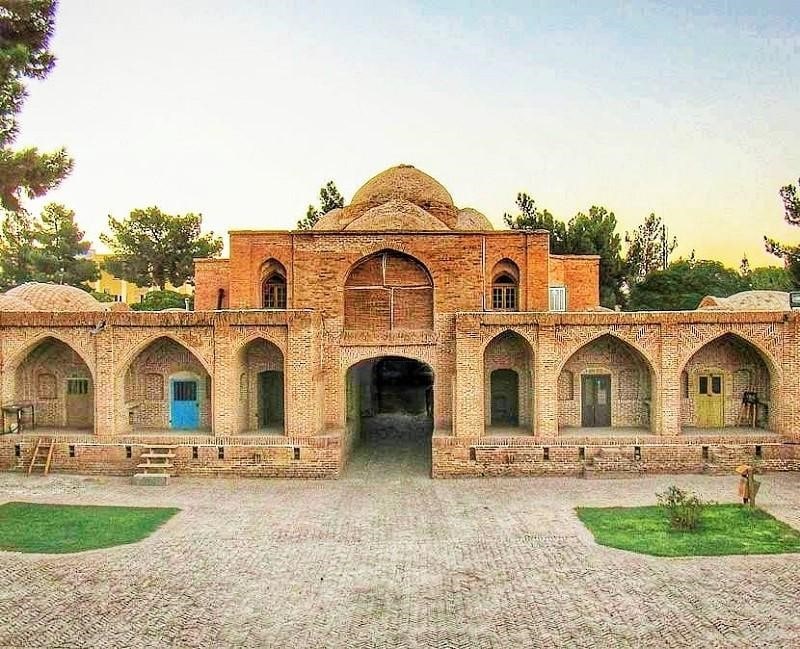

Iranian Caravanserai

The word Karevansara or Caravanserai is a combination of two words Kareban (travel convoy) and Sara (home inn). Both are Pahlavi words that originated in the Sassanid period. There are no remains of pre-Islamic caravanserais in Iran, and traces of their existence can only be found in historical accounts. For example, Herodotus mentioned 111 Manzelgah (rest stops) between Shush and Sardis. During the Parthian era, Parthian Chapar Khanehs were built for travelers to rest. After Islam, the number of caravanserai increased significantly. In his travelogue, Marco Polo mentioned three caravanserais in the Yazd desert.

Deyre Gachin Caravanserai in Qom, Zizeh in Kashan, and Robat Mahi in Mashhad are some of the most famous historical Iranian caravanserais.

Tombs

The Tepti-Ahar tomb is one of Iran’s most ancient tombs. Catacombs are a type of tomb structure that existed in Iran before the Achaemenid period. The tomb of Cyrus the Great is a prominent example of pre-Islamic tombs in Iran. Due to Iran’s monotheism in the Sassanid era and according to Zoroastrianism, burying the dead in the ground was forbidden. That’s why despite their grand and majestic lifestyle and the utilization of Iranian architecture in their palaces, there are no historical tombs of Sassanid royalty.

After Islam, despite the Prophet’s opposition to building tombs, the construction of tombs and mausoleums became very common. The tombs were built with square, octagonal, and round building designs, and like other buildings of the Islamic period, they were decorated with tilework, mirrorwork, and such decorations.

Ismail Samani Mausoleum in Bukhara, Gonbad-e Qabus Tower in Golestan province, and Dome of Soltaniyeh in Zanjan are prime examples of famous historical tombs in Iran.

Schools

The remains of the oldest educational center in Iran, which can be called a school, were found in Shush and belong to the second millennium BC. The objects discovered from later periods also show the importance of education among Iranians. The most prominent place of pre-Islamic education in Iran is the Academy of Gondishapur or Gondishapur University.

After Islam, mosques became a place of basic education. But independent schools were built during the Seljuk era and with the efforts of Nizam al-Mulk. The schools had a plan of four-Iwan(hall) designs. One or two-story chambers were built around the Iwan for student accommodation. Like mosques, schools were decorated with brickwork and plasterwork.

Khargerd Ghiasieh School in Khorasan Razavi province, Chahar Bagh Theological School in Isfahan, and Shahid Motahari Univesity in Tehran are examples of schools with traditional Iranian architecture.

Minarets

Minaret means place of light. Before Islam, minarets were a place to light fire and guide travelers and sometimes served as beacons for fire temples called Mil. Later, these minarets were placed next to mosques to announce Adhan (call to prayer). Minarets are also used to fortify the building foundation and prevent landslides.

It is not hard to accurately pinpoint the oldest minaret in Iran. Perhaps the column in the center of the Ardashir-Khwarrah ancient site in Firouzabad, Fars province is one of the only remnants of traditional Iranian minarets from the early Sassanid era. But in the post-Islamic era, the minarets of Semnan Central Mosque and Grand Mosque of Damghan seem to be the oldest minarets in Iran.

At first, one minaret was built for a mosque, but since the Seljuk period, the construction of dual minarets became common. Minarets consist of three parts: base, body, and alem (spire).

Bazaar (Traditional Iranian Market)

Bazaars or permanent marketplaces have been a social center of trade and human interaction since ancient times. Let’s take a brief look at how traditional Bazaars formed and review their role in urban design in Iranian architecture.

The first Bazaars in Iran emerged in the form of adjacent chambers in one row or two opposite rows. Over time, roofs were built over the passage in the middle and domes were built at the intersections, forming Charsoo (cross) passages. Different parts of the Bazaar developed based on different demands where a diverse inventory of goods was available for purchase.

Iranian Bazaars that were located near major trade routes such as the Silk Road developed more than others and became import and export centers. Therefore, structures were built in the middle of the Bazaar to store goods, accommodate traveling merchants, etc. In addition, markets were the heart of every city’s economy and played a major role in urban design and the development of commercial and residential districts of cities. Sometimes Bazaars included the Friday mosques of the cities, Zoorkhaneh, schools, and other significant establishments.

Vakil Bazaar in Shiraz, Tabriz Grand Bazaar, and Zanjan Great Bazaar are among the traditional Bazaars of Iran.

Indigenous Iranian Architecture

Over the past centuries, the indigenous populations of each region in Iran have designed and constructed buildings based on personal needs and preferences, and regional climates. In that context, there are four types of structures that are entirely Iranian, which we will introduce below.

Ab Anbar (Cistern)

The history of Ab Anbar or water reservoirs in Iranian architecture is not quite clear. Evidence suggests that back in the Sassanid period, Cylindrical beam-supported water reservoirs were built by prisoners of war from the Mediterranean region. Of course, the Iranian plateau is mostly a dry region, and storing water in Ab Anbar is a great solution to conserve water. Many standing Ab Anbar buildings today date back to the Safavid era. The main parts of the Ab Anbar include the source, Pasheer (the lowest point in the Ab Anbar stairway and the access point to the water, stairway, portal, ventilation point, and wind catcher.

Khajeh Khezr Ab Anbar in Yazd, Haj Ali Agha Ab Anbar in Kerman, Vazir, and Mirza Moghim Ab Anbar in Isfahan are examples of Indigenous Iranian Architecture.

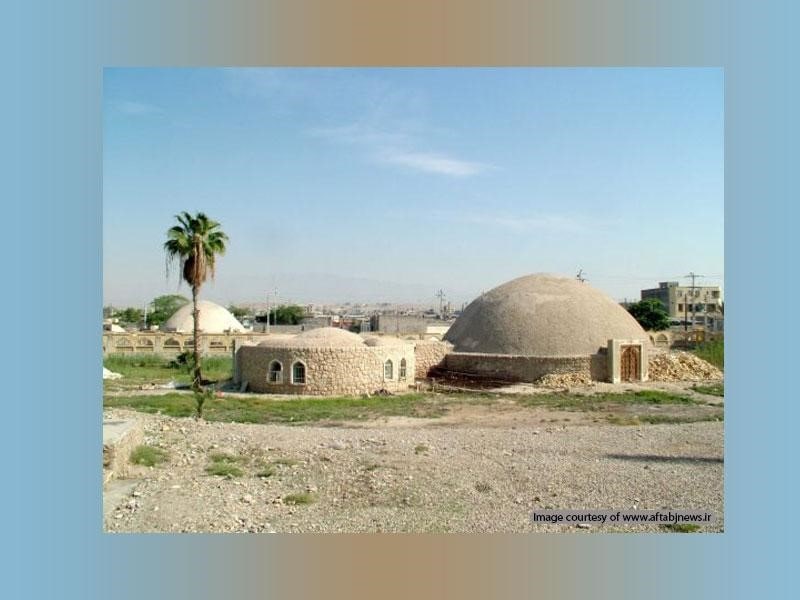

Yakhchal (Ice Pit)

Yakhdan or Yakhchal (Yackh: Ice + Chal: Pit) is a structure type in ancient Iranian architecture designed to produce ice in the winter and store it for summer. Usually, each Yakhchal had a pool and a high wall, a barrier, and a Khazaneh (domed tank). The barrier’s shadow would cast over the pool all day and keep it cool. The ice that was made in the Yakhchal pool in the winter was broken into pieces and stored in the Khazaneh and used in the summer.

Yakhchal buildings grew popular in the Safavid era, and there is not much information about traditional Yakhchal buildings before this period.

Badgir (Windcatcher)

In adaptation to Iran’s hot and dry climate, ancient Iranian architects invented the Badgir or wind catcher. Each wind catcher includes a ventilation tower on top of a base structure. There are a series of vertical openings on top of each tower that direct the wind into the building. Wind catchers are common in Kashan, Yazd, Bam, Jahrom, Tabas, and on the coasts of the Persian Gulf.

Kabootar Khaneh (Dovecote)

Kabootar Khaneh or literally pigeon house is also known as Kaftar(dove), Pigeon Tower, Vardeh, or Hammam Tower. It is one of the ancient Iranian structure types. These towers were built to collect the feces of pigeons. In the past, bird feces were used as fertilizer in agriculture and had other uses in tanning leather, and making gunpowder.

The Kabootar Khaneh building is usually between 7 and 15 meters high. There are rows of identical bird nests inside these towers and they could easily enter or leave the pigeon house. The structure was designed to prevent hunting birds such as hawks and rams from entering the nests. There are many pigeon houses around the city of Isfahan and Meybod in Yazd Province.

Design Elements in Iranian Architecture

Over the ages and in harmony with the climate and the needs and preferences of the people, indigenous Iranian architecture has developed design elements that are considered the defining characteristics of Iranian architecture. In the following, we introduce some examples of these design elements.

Gonbad (Dome)

The history of the Gonbad design in Iranian architecture goes back to pre-Islamic Persia. The stability of the dome on a square-shaped building requires precise calculations that demonstrate the mathematical intelligence and architectural knowledge of Iranian designers. Usually, they used a polygonal cornice to connect the square base to the dome. After Islam, the jewel of the building was considered its dome, usually decorated with tilework.

Iranian domes were made in different styles; Such as cone-shaped or Rok domes, one, two, or three-layer dome shells, and attached-shell domes and unattached shell domes (referring to the construction of dome shell layers).

Iwan (Large Hall)

Iwan or Eywan has been present in Iranian architecture since the Parthian era and has been implemented in different designs with various applications. The Iwan is the exterior part of the building and usually consists of a barrel vault that is closed off on three sides and opens to the Miansara (central hall). Iwans block sunlight while creating airflow inside the building. Iwan is the shining front in the facade of a mansion and is often decorated with brickwork and plasterwork designs.

Before Islam, Iwan was an elite feature for royal mansions, religious buildings, and royal administrative establishments. With the arrival of Islam, this ancient Persian design element was adopted in the architecture of ]Iran mosques and Muslim mausoleums.

Iwan-e Madaen or Taq Kasra is one of the most unique masterpieces of Iranian architecture. The Iwan in this Sassanid-era historical attraction is about 43 meters wide and 30 meters high. Although this building has been the victim of various unfortunate events over the years and parts of it have been demolished, it still has its timeless magnificence.

Mosque Mihrab (Altar)

Mihrab is called a vaulted vertical niche built into the mosque wall. At first, the purpose of its construction was to honor the Prophet’s prayer site, and later it found a new function: to show the direction of the Qibla to the worshipers. Bricks, tiles, and mirrors were meticulously arranged by the hands of Muslim artists to decorate Mihrabs. All mosques have at least one Mihrab. Jameh Mosque of Isfahan has 9 Mihrabs.

Mosque Minbar (Pulpit)

The origin of the Minbar design is not very clear. Some researchers consider the minbar as a monument of the high ground where a king or the prophet would stand to address the crowd. Since the early days of Islam, rulers sat would sit on thrones and address their supporters. Unlike the mihrab which can be seen in all mosques, a minbar is not present in all mosques.

Shabestan (Prayer Hall)

Shabestan is a roofed area often built with uniform rows of parallel columns. Most Shabestans are connected to the mosque courtyard from one side. Shabestans are built on two or four sides of the mosque. Sometimes there are mosques with a single Shabestan, Where the prayer hall is built in the south of the mosque and in the direction of the Qibla. The number of Shabestans in a mosque depends on the expected number of worshipers and the significance and stature of the mosque.

Hozkhaneh (Fountain House)

Hozkhaneh is a summer dwelling in Iranian architecture that usually has an octagonal shape. There is a small fountain in the middle of the building, and the water keeps the air humid in dry seasons and cools the Hozkhaneh. Sometimes a Badgir or wind catcher was built above the fountain and directed the cool air to the water reserve. There are two styles of Hozkhaneh construction:

- Open Hozkhaneh: in the open fountain house design, one side of the fountain faces the courtyard. The courtyard porch casts a shadow over the building that keeps the outside heat at bay. Also, the flowers and trees in the courtyard garden act as natural ventilation.

- Closed Hozkhaneh: in the closed fountain house design, the building is not directly connected to the courtyard and is often surrounded by rooms

Decorative Art Styles in Iranian Architecture

Iranian architecture has achieved such prominence over time and with the efforts of hardworking and masterful architects. Iranian architecture is the art of attention to detail and meticulousness. In the following, we will introduce some decorative arts that are used to decorate and adorn buildings in Iran:

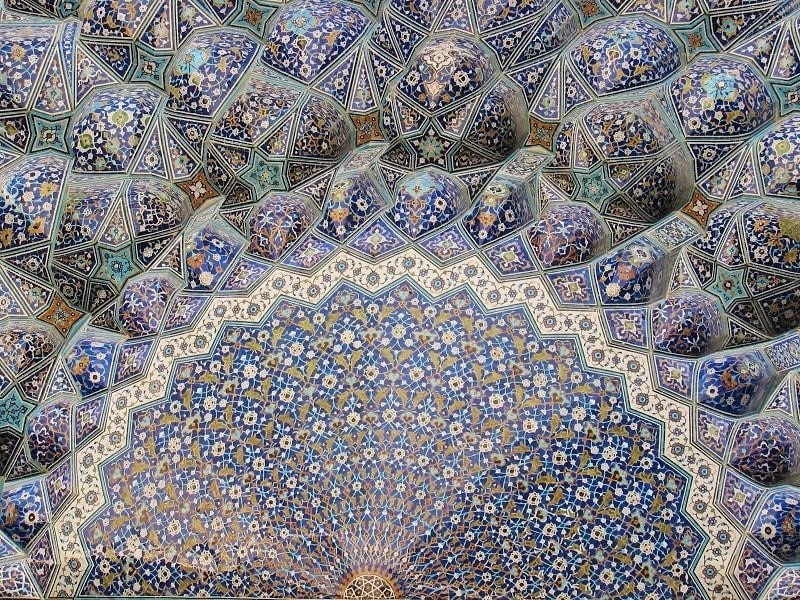

Iranian Kashi Kari (Tilework)

The first Persian Kashi examples or Iranian tiles from the pre-Islamic period were left from the Elam Ancient Civilization. These tiles were made in the form of glazed square baked adobes with embossed designs.

Tilework played an important part in building decoration after Islam and there are traditional tilework examples with single-color or seven-color designs, Kashi Mo’araq or mosaic designs, and tilework designs that include brickwork. Various parts of the buildings, such as the dome, wall, Minaret, and Mihrab, were decorated with tilework decorations, and this art continues to thrive today. Goharshad Mosque, Masjed Kabood or Blue Mosque in Tabriz, Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque in Isfahan, and Jameh Mosque of Gonabad contain some of the finest examples of Iranian tilework.

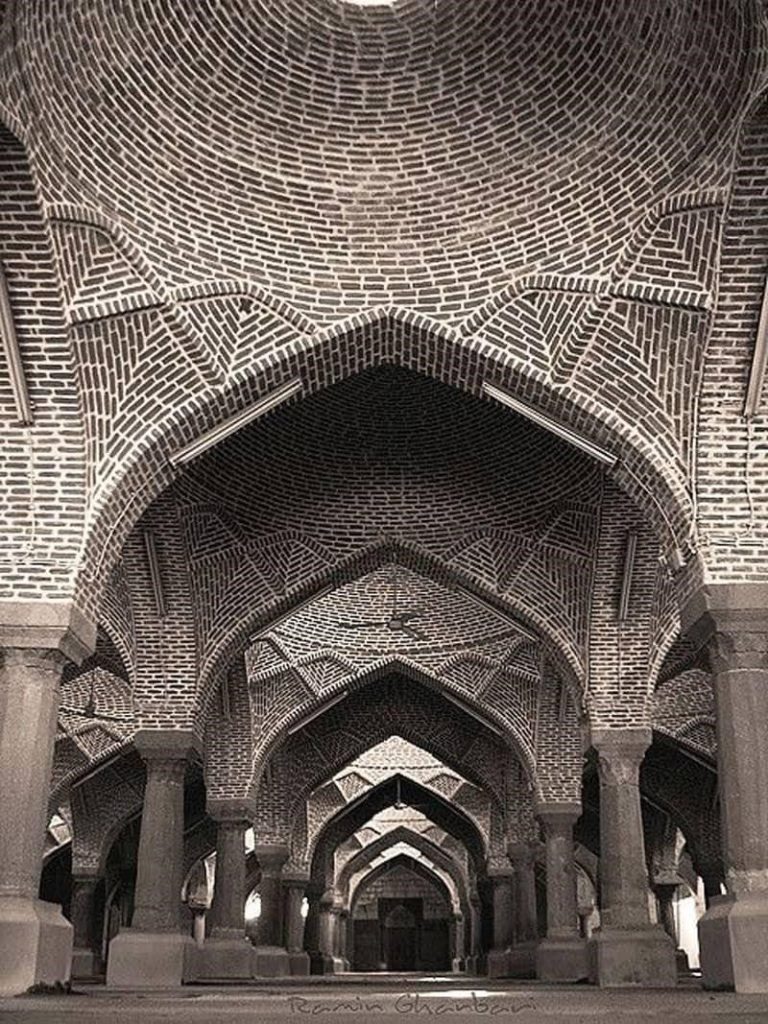

Ajor Kari (Brickwork)

The history and origin of brickwork and its use in Iranian architecture can be traced back to ancient Persia. In addition to its use in forming structures, brick is also used in decorating buildings. Since the arrival of Islam in Iran up to the Timurid era, most of the buildings are decorated with only brickwork. Beautiful brick buildings have been left from the Seljuk period.

Bricks have also been used in the construction and decoration of domes. The brick Dome of Soltaniyeh from the Ilkhanid era is one of the magnificent examples of this art that influenced the church designs in the Middle Ages. Different mixes of Ajorchini Khofteh Rasteh (header and stretcher brick bonding method) and Ajorchini Jenaghi (raking bond method), and the combination of brickwork and tilework are common styles in traditional Iranian brickwork.

Gach-bori (Plasterwork)

Gach or plaster has been one of the first abundant materials available to Iranian artists and craftsmen. Plaster is malleable and rapidly hardens, which gives artists the opportunity to create what they want easily. Since the Sassanid period, the art of plasterwork has been used to decorate palaces and buildings. The designs used in plasters were often inspired by plants and animals. After Islam, in order to avoid recreating animal figures which would constitute idols, this art style became more abstract and subjective. Plasterwork artists used different practices such as colored plaster, Vasleh or plaster fragments, solid and hollow plasterwork, and relief or stucco plasterwork.

Oljaitu Altar in Isfahan, Alaviyan Dome in Hamedan, and Dome of Soltanieh in Zanjan are masterpieces of Iranian plasterwork artists.

Āina-kāri (Mirrorwork)

Ayneh Kari or Mirrorwork is one of the building decoration techniques in Iranian architecture. It manifested after the arrival of Islam, especially in the Safavid and Qajar periods. The Ayeneh-kar or mirrorwork artist assembles large and small mirror shards in order and places them on the mirror base in special geometric patterns to create a unique artwork. In this art, mirror pieces are attached together at a slight angle to reflect light from different angles, similar to a kaleidoscope.

This craft was used in the decoration of window frames, walls, ceilings, and columns in private mansions, teahouses as well as royal buildings and shrines.

The house of Shah Tahmasp Safavid in Qazvin, the Kahk Ayneh Khaneh or Mirror Palace in Isfahan, and the Shah Cheragh Shrine in Shiraz are some of the magnificent examples of mirrorwork in Iranian architecture.

Muqarnas (Mocárabe)

Muqarnas or Mogharnas is the assembly of small fragments placed on top of each other in a certain order that gradually come up from the base walls up to the top of the ceiling or “Shamseh” and create an ornamented and convoluted ceiling design. Muqarnaswork is usually utilized under entrance and Iwan vaults, in the Ghooshvareh or squinches of domes and, corners of Iwans. Sometimes the whole ceiling is decorated with Muqarnas. Muqarnaswork can be seen in column capitals, minarets, facades of towers and interior decorations of rooms.

Although it looks very complicated at first glance, Muqarnas designs are made up of simple geometric patterns. Muqarnas emerged in Iranian architecture during the reign of the Samanid empire and was mostly reserved to decorate mosques.

Fresco or Wall Painting

Cave walls were the first places where humans painted. In the very distant past, Iranians used a mixture of fruit extracts and iron oxide to paint buildings. Usually, the art of painting is performed on freshly coated plaster on walls, plasterwork surface, or murals.

Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sassanid palaces were also decorated with this art. After Islam, Fresco and wall painting flourished during the Timurid era.

In the Safavid period, oil paint was used to paint large wall paintings. Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque and Aali Qapu Palace are some of the prominent Safavid buildings decorated with fresco wall paintings.

The History of Iranian Architecture

Iranian architectural styles are inspired by the materials available in the country. In ancient times, Iranians made primitive clay molds and filled them with hard clay, hard plaster mortar, and bricks and stones. They built big and beautiful Tells (mounds), whose smooth and wide surfaces drove artists to create decorative art.

Even after 3 thousand years, some elements of ancient Iranian architectural design are present in modern Iranian architecture. These elements are large doors with tall magnificent entrance vaults, columns with wall-mounted capitals, halls, Chahartaq (four-vault) dome, large oval-shaped vaults, Chahar-Iwan (four-hall) courtyard, basic high towers, an interior yard and pool, indirect entrances and extensive decorations.

In addition to the climate, available materials, religious ideals, and local culture, historical figures have also played an important role in the development of Iranian architecture.

Natural landscapes, snow-covered mountains, vast valleys, and boundless plains of the Iranian plateau left an impression on the mind and soul of the Iranian architect, which has been reflected in their works. Mountains have been a source of inspiration in Iranian architecture in both a physical and symbolic sense.

After the popularization of the Zoroastrian religion, the concept of beauty was associated with light. Iranian art has always strived to convey light and clarity, and at the same time, avoid dark and desolate designs. For ancient Iranians, like other ancient civilizations, beauty was considered a divine attribute.

Primitive Iranian Architecture

In order to identify the roots of the main elements of Iranian architecture, such as arches and vaults, and domes, we must go back to before the arrival of the Aryan tribesman to the Iranian plateau.

Agricultural villages discovered in Iran from 6,000 to 8,000 years BC are the first known entries in the history of Iranian architecture. Ancient graveyards can be considered the first signs of intentional architecture. Goor Kharposhteh in Kashan’s Tepe Sialk is the first example of fortified vault architecture.

There is also a graveyard of a Scythian tribe in the north of Lorestan on the ancient hill of Ziwiyeh Castle. This grave is the first recorded attempt to create a circular design in the 9th and 10th centuries BC.

The prehistoric village of Sialk is considered the first architectural phenomenon in the fifth millennium BC. The walls in the Sialk village were built with riprap stones, Sarooj mortar, and limestone. Iron oxide and fruit extracts were used to paint the walls.

Later, Sialk people discovered how to make baked adobe. They shaped the clay by hand and dried it in the sunlight. They made grooves on the surface using their fingers before the clay fully sets. This made the bricklaying process and applying mortar easier. Later, the village of Tepe Sialk became a fortified town with a watchtower, bailey, and battlements. There were social divisions in the city, and even the graves were marked.

Elamite Architecture

In the third millennium BC, the Elam civilization thrived in Mesopotamia. They were a powerful kingdom before the Achaemenes rose to power. Graves with arched vaults have been found in Haft Tepe archeological excavation sites. The baked adobe vaulting style in these graves is still popular today with the same principles and is known as “Korepoosh” or cradle vault.

The ChoghaZanbil Ziggurat is a relic of ancient Elam architecture, which can be considered part of the foundations of Iranian architecture. 1500 years before the Romans, the Elamites learned the technique of making an arched vault.

Elamite architecture generally employed raw adobes and red bricks were used in bricklaying walls. A few centuries before the rise of the Medes, two or three stone walls were built in the northwest of the cities. Larger and taller buildings supposedly had wooden, square-shaped, tower structures with columns. These structures were probably made from tree trunks.

Medes Architecture

During the gap between the Elamite civilization and the Medes, the invasion of various tribes such as the Urartu left no valuable architectural remains intact except for the citadel in Teppe Hasanlu.

Traces of Medes architecture can be found in some parts of Iran, such as Azerbaijan, Hamedan, and Kurdistan, which can be divided into three categories:

- Normal architecture, with scattered and separate houses divided by farms

- Citadel or Castle architecture where several families lived together

- Rock-cut architecture in the mountains, sometimes in the form of a crypt, where the dead were laid to rest.

The first magnificent architectural work of the Medes was a nested castle in the city of Hegmataneh, modern-day Hamedan. It has been mentioned by famous ancient historians. Herodotus has written about this castle: “The royal palace of Hegmataneh has a strange and strong standing and is built as seven castles inside each other. Each castle is inside enclosed by another castle, and the seven baileys are painted in different colors, the exterior castle was white, and their others were in order black, purple, blue, red, silver, and gold (the innermost castle was the Shahneshin or the king’s residence).”

During this period, houses were generally larger, and following the invention of bricks, the walls were better arranged. Building a window facing the courtyard and using large pieces of baked clay as waterproof coating are some of the architectural advances of the Medes civilization.

The Rock Tomb of Fakhrigah, Bistoon Crypt, and Dukkan-e Daud Crypt are historical sites left from this juncture in Iranian Architecture.

Achaemenid Architecture

With the rise of the Achaemenid Empire and especially Cyrus the Great, many political and social developments took place in Iran. Progress in art, architecture, and urban planning and design were among these developments.

Achaemenid architecture drew inspiration from other civilizations, creating a unique combination of architectural designs from different civilizations such as Median, Assyrian, Elamite, Egyptian, Ionian, and Urartu. What distinguishes Achaemenid architecture from its sources of inspiration is the special style of combining their elements with indigenous styles and preferences.

The architectural style of the Achaemenid period is known as the first Persian style. Of course, there are only minuscule traces of civilian houses from the period remaining today, and palaces and royal buildings are often the basis for defining the Achaemenid architectural style.

There were three important elements in Achaemenid architecture that can be considered Persian in origin: columns, stone tombs, and stairs.

While there are columns in the remains of previous civilizations, the columns built during the Achaemenid period were the most delicate columns of their time. Achaemenid columns were used as decorative elements. These columns were tall and were built with rather large gaps. Their architecture could not have been possible w precise calculations

In this period, clean-cut and sometimes polished stones were used in construction. Architects first built a solid platform with riprap stone and gravel and other materials that would serve as the foundation for the building. The interior walls were decorated with glazed tiles and the floor is decorated with the best materials. Entrance portals and capitals were decorated with magnificent relief statues. The construction of beautiful large gardens and pools is another architectural feature of this era.

Also, they invented the Chahar-taq or four-vault design for their fire temples, which was later used in the construction of mosques.

Gur-e Dokhtar ancient tomb in Bushehr, Tomb of Cyrus the Great, Pasargadae, Apadana Palace in Shush, and Takht-e Jamshid (Persepolis are examples of the First Persian style of Iranian architecture.

Seleucid Architecture

During the Seleucid period, Greek designs became more dominant in Iranian architecture; But they were never fully adopted. In areas with the most Greek and Macedonian populations, urban areas were planned based on Greek geometric designs, temples were built with the impression of Greek examples, and unique design elements of Greek architecture were also used in building decoration.

Seleucid Empire architecture had a Greek undertone, but the construction of urban structures and areas was inspired by ancient Eastern architectural traditions. These cities usually had a square or rectangular plan (Hippodamus) and perpendicular streets. The Greek-dominant cities of the Seleucid Empire were equipped with facilities such as markets, stadiums, and theaters.

Historic neighborhoods in Antakya in the south of Turkey, Seleucia in Iraq, Ai-Khanoum in Afghanistan, and Taxila in Pakistan are examples of the cities of the Seleucid period.

Parthian Architecture

The Parthian or Arsacid rise to power brought an end to the dominance of Greek influence over Iranian architecture. At the beginning of the rise of the Parthians, Seleucid style was still the major style of Iranian architecture, and from the time of Mithridates II or Mehrdad II in 124 BC, the Parthian architectural style gradually developed.

During the Parthian period, the cities were built in circles, enclosed by rampant and fortified watchtowers. In order to adapt to the many threats endangering the empire, Parthian architects prioritized security and military strategies in the construction of cities. The composition inside the cities was made up of three parts, the citadel (Kohan-dej or old fort), Sharestan or the fortified inner city, and outside.

The Parthians built the great ancient city of Tisphon or Ctesiphon. The circular expansion and construction of palaces in that city continued until the end of their rule. This city was the capital of the Parthian Empire and later the Sassanid Empire.

Since the Parthians were originally a warrior nomad tribe, they built cities that could hold defensive positions against military offensives from any direction. Roman Ghirshman believed that the Middle Ages architects imitated this practice from Parthian urban design.

During the rule of the Parthians, an element called Iwan (rectangular hall) appeared in Iranian architecture. The development of clay dome brick bond techniques using baked adobe, an Elamite invention, was a special feature of this era. The walls and ceilings were decorated with plasterwork. Darabgerd ancient city in Fars, the Parthian Fortresses of Nisa in Turkmenistan, and Mount Khajeh in Sistan are among the ancient cities from the Parthian era.

Sassanid Architecture

The architecture of Iran during the Achaemenid period is mostly developed based on the architectural styles of the north and west of Iran, while the Sassanid architecture is based on the indigenous architectural style common in the central and eastern dry regions of Iran. If we consider sturdy and delicate columns symbols of Achaemenid architecture, then Taq (vault) and Gonbad (dome) are the symbols of Sassanid architecture. In Sassanid designs, dome covering is more common in Chahar-taq or four-vault buildings and Taq-e Zarbi and barrel vault ceilings. Palaces and fire temples are beautiful manifestations of Iranian architecture in this period.

Iwan in Sassanid design was a very large hall that served as the welcoming area, leading visitors to the domed areas. These areas were also used as meeting halls. These were examples of Sassanid architecture that have been repeated in many palaces. Plaster was used in building construction during this period. Because it dried faster and, therefore, helped to build a barrel vault without the need to install any scaffolding.

The walls were decorated with relief carvings and wall paintings and other decorations. In general, floors and walls were decorated with large colorful tiles. As a result, designs were more repetitive and extensive.

The art and architecture of Iran during the Sassanid period remained popular long after the end of their empire. The Khorasani and Razi styles also emerged as the main schools of architecture in the Second Persian Empire or the Sasanian era.

The Palace of Ardashir, Bishapur Palace, Sarvestan Sasanian Palace in Fars province, and Iwan Madaen or Taq Kasra in Iraq are prime examples of Sassanid buildings. In this period, the fire temple architecture rose to new heights. The Chahar Ghapi Fire Temple in Qasr-e Shirin, Azargoshnasp fire temple in Takht-e Suleiman, and Adur Burzen-Mihr Fire Temple in Khorasan are some of the fire temples of this period.

Islamic Iranian Architecture

In Iranian architecture after the arrival of Islam, the emphasis was on mosque construction. Mosques had to be built with durability, to stand the test of time. For this reason, these buildings were the most stable buildings in Islamic architecture.

Since that time, the construction of mosques began in two main styles:

- Mosques with column-supported prayer halls(Shabestan)

- Smaller mosques with dome vaults

Iranians tried to maintain their architectural heritage; elements such as barrel vaults, roofs with small serrations, cone-shaped squinches, large bricks, and oval arches. Brickwork and different brick bond methods and sometimes plasterwork on bricks. These are only some of the elements of Islamic Iranian architecture. The construction of different types of tombs and tomb towers, or customized tomb towers and minarets were common in this era.

Iranian architectural style in the first to fourth centuries after Islam is known as the “Khorasani style”. The Khorasani style was inspired by the Sassanid School of Architecture. The construction of arched vaults in this period was an imitation of the famous Taq Kasra. Jameh Mosque of Fahraj and Tarikhaneh Mosque in Damghan are examples of Khorasani-style architecture.

Seljuk Architecture

The Seljuk era was a period of brilliance in Iranian art, especially Iranian architecture. A thousand years have passed since that period, But the buildings from that era show the skill of the architects of that period in building beautiful and robust buildings. During this period, schools were separated from mosques for the first time. The schools of this period were often built with four Iwans.

The architectural style of this period is called the “Razi” style. This type of architecture was more observed in the city of Rey. The Razi style of architecture has both the precision of Khorasani’s style and the splendor of Parthian designs. Later in the Seljuk era, the number of tomb towers and minarets surpassed the number of mosques. However, building mosques was still the main focus of Islamic Iranian architecture. The dome vault style mosques became the dominant type of mosque. Later, the four-hall plan became the dominant style of mosque design.

The double-shell dome and the Groin vaults were designed in this period. The use of dark and light blue glazed brick and clay made the architectural structures brighter and improved the visibility of brick inscriptions. Mosaic tilework with single-color tiles became popular until the end of this period. The Seljuk period is known as the period of revival of Islamic art and civilization in Iran.

Ilkhanid Architecture

During the Ilkhanid period, many artists and architects in Khorasan were killed by the Mongol invasion. For this reason, the Ilkhanid court brought in architects from Azarabadgan (modern Azerbaijan) to build buildings. These master architects were also sent to Samarkand, Bukhara, and Central Asia to oversee the construction of other historical monuments. That’s how the Azari architectural style became popular in the Ilkhanid era.

About 90% of the buildings left intact from the Ilkhanid period are religious establishments and the rest are tombs. Perhaps the most outstanding feature of Ilkhanid architecture was its willingness to adopt common designs of the Seljuk period.

Iranian architecture during the Ilkhanid era utilized mosaic tilework using tiles with new bright colors and shiny tiles to cover the lower parts of the wall.

Timurid Architecture

During the Timurid rule, Iranian architecture had special features; Including:

- A combination of dark and light and monochromatic glazed tiles in building facades

- Raised vaults decorated with sharp-edge mosaic tilework

- Different types of dome construction and the precise calculation for very large domes became an integral part of Iranian national monuments

Domed buildings inspired Timurid-era architects to practice dome construction. Dome bases became taller than previous examples, and the domes were designed in the shape of special signs and symbols. The dome exterior was decorated with tilework with various designs and calligraphy. These designs were enhanced under the influence of the Chinese art style.

Safavid Architecture

During the Safavid era, a network of caravanserais was established in the country to make transportation easier and promote trade. Safavid architecture influenced the construction customs of other countries. Emphasis on the large size of the buildings, which started from the Timurid era, remained one of the principles in many architectural constructs of the Safavid period. Radial symmetry was implemented in formal buildings as an impressive feature.

There was a strong desire to build sunken structures, such as niches in the wall or even pit entrances, and create a contrast by adjusting the size or lighting of design elements. Undoubtedly, color played a pivotal role in Safavid architecture. Compared to the previous era, tilework covers were applied to more surfaces. Decorating the space had become a priority for architects.

Iranian architecture in the Safavid period was the peak of the skill and experience of Iranian architects. Despite their traditional tools, the structures were built flawlessly on such large scales. Many efficient and practical structures were also built such as bridges, markets, baths, water reservoirs, dams, dovecotes, and caravanserais.

Zand Architecture

The Zand dynasty promoted an architecture style that studied the Safavid, Seljuk, and pre-Islamic styles of architecture, but was also inspired by Indian and European architecture.

What was most innovative about this era was the use of glazed tiles in new colors, such as the use of pink tiles known as Zand tiles. Vases made of stone were installed at the bottom of the wall, and painted tiles and cornucopia designs were also implemented.

The horn of blessing or cornucopia is a symbol of abundance and blessing, which is depicted as a large horn overflowing with fruits and vegetables, flowers and plants, nuts, and other foods. The horn of plenty has its origins in Greek mythology and is still used as a symbol in Western art. This symbol is also used in some relief artworks from the Parthian period.

Qajar Architecture

Many mosques were built during the Qajar dynasty. These mosques were vast with four-hall plans, and a network of Qobbeh (cupola) and windows were added to their design to illuminate the building. Many Safavid buildings were poorly restored during the Qajar era. The architects of that period introduced new trends into Iranian architecture; Like sunken courtyards and exaggerated onion domes and decorated gateways around large cities.

Qajar buildings include many palaces, mansions, Kushks (huts), summer resorts, hunting resorts, and also administrative buildings. Military architecture became the focus of Iranian architects during the Qajar era. The decorations remained harmonious and flawless. They were influenced by the Western world and also tried to imitate Sassanid Art. Ceilings with magnificent decorations and halls decorated with mirrorwork became popular during this period.

Iranian Architecture, Timeless Indigenous Art

Iranian architecture is a sign of the soul and culture of Iranian people over time. You can observe the ancient history of this land in the frame of the remaining buildings from different periods.

The Iranian architect was not looking for material gain. He spent his life and soul as material to build every building and poured his heart and mind into clay, plaster, and mirror to create a building for the comfort of the human body and soul. Conscious travel to any historical monument is actually meeting the spirit of its artist and the history of Iran and Iranians.

Frequently Asked Questions About Iranian Architecture

To find answers to your other questions, you can contact us through the comments section of this post. We will answer your questions as soon as possible.

In what period was the style of ancient Persian architecture popular?

The ancient Persian style was an Iranian architectural style popular in the Achaemenid and Sassanid periods and is known as the “Persian” style.

What are the characteristics of indigenous Iranian architecture?

The indigenous architecture of Iran is introverted, self-sufficient, and human-oriented, utilizes local materials, and avoids waste.

Is Iranian architecture inspired by the architecture of other countries?

During the Achaemenid period, inspiration from the architecture of other civilizations and combining it with the architectural patterns from Media, Assyria, Elam, Egypt, Ionia, and Urartu. Since the Qajar era, our architects were inspired by the West, and with the beginning of modern architecture in the West, we were also inspired by them.

During the Pahlavi period, this tendency intensified, and valuable architectural artworks were created in Iran.

Why is the traditional architecture of Iranian houses different from other architectural styles in the world?

Due to the hot and dry climate of the central plateau of Iran, unique architectural practices formed in our country, with the innovation of Iranian architects. The use of materials such as clay, brick, and plaster, as well as the invention of traditional cement (Sarooj) grew popular and resulted in the development of a special style of architecture that inspired other countries in the region.

In the mountainous regions of the northwest and west, another style of architecture emerged using riprap stone, straw, and other available materials suitable for the cold winters of that region.

Are we currently witnessing the combination of Iranian and modern world architecture?

Iranian architecture, like other manifestations of Iranian culture, is interacting with other indigenous and modern architectural traditions and styles in the world. As a result of cultural interactions, Iranians have also been inspired by modern global architecture.

Except for a few examples in which climate conditions are considered, today we are witnessing the evolution of Iranian architecture in combination with modern architecture and also drawing inspiration from it in accordance with available construction materials and climate conditions. What can guide this process in the right direction is the leadership of dedicated institutions and the preservation of Iranian architectural heritage.