In ancient times, coins were minted as a means of governmental or religious propagations and rarely as fixed means of facilitating business. Therefore it’s not easy to follow a well-defined history of coinage in Iran.

Little by little, people got to find out money’s real function. Since then, people started to exchange money for goods. Therefore, money minting began as the production craft by the local as well as central governments.

Coinage Development in Pre-Islam Period

At about 515 B.C, In Iran, the first Iranian coins were ordered to be minted by Darius I, Achaemenian emperor. There were depicted a warrior holding a bow on the front and a quadrangular sign on the back of these coins. Achaemenians’ gold coins were called Darick equal to 20 silver coins. This lasted for 200 years.

Parthian kings, as a result of Hellenization, minted 4.25 g silver coins called Drachmas, Athens standard. There were both silver coins and copper coins minted by them. Frequently, in each historical period, there was an original pattern for coins and later other modifications were implemented.

Usually, on the back of Parthians’ Drachma, there were patterned the founder of the dynasty, Ashk I, for example, sitting and holding a bow in his hands, similar to Seleucid coins patterned by embossed Apollon sitting on the spherical stone of Delphi temple.

The minting of Sassanian coins dates back to 499 A.D. Hellenistic civilization is obviously indebted to coin minting to Sassanian Pioneers. Sassanian coins were clearly innovative and purely Iranian. They did not follow or imitate their predecessors. For the first time in the history of coinage, thin flat circular metal made coins were minted.

They were later used as well-decorated and current coins in Arab regions, Byzantine Empire and the Middle Ages Europe. The vividly pictured profile of the king was patterned as he was looking at left. Personal facial features were clearly seen. King’s name was also mentioned in Pahlavi in front of his face. The back of coins has always been symbolically used for religious purposes, as still functional in Iran.

On Sassanian coins, a fire altar in the middle with its fire flames blazing patterned this side. There were often two fireguards on both sides as well.

Coinage Development in Post-Islam Period

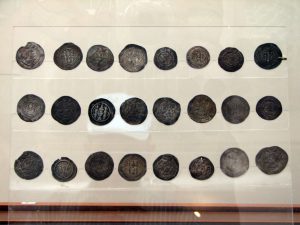

The coins used during long sovereignties of Khosrow II and Yazdgerd III were still widespread after Arabs’ invasion, especially the coins minted during Khosrow II, which were in use with little modifications toward the end of the 7th century as main models for silver coins.

In the post-Islam period, some coins, called Arab-Sassanian, were in use till around 650 – 700 A.D. The name and title of Arab rulers replaced the Iranian King’s in Pahlavi and a religious word or two or prayer formed the Arabic lettering on coins. The dates on the coins were from three various calendars: One lunar calendar and two Yazdgerdy calendars, one beginning with the date of his coronation, the other with his death.

Around 100 years after Arabs’ invasion, the Islamic world started to mint coins experimentally. A Caliph with his sword in sheath, Islamic witnessing phrases and a Caliph standing with his hands in form of prayer were different patterns and letterings on the coins.

Between 696 and 699 A.D, Abdolmalek, an Arab Caliph, made a radical change in coins and introduced Islamic doctrine in coinage by saying no to idols (portraits of rulers faces), banning the picturing of living beings and prohibiting luxury. Instead, religious words filled the whole surface of coins except for the date and place of coinage. Arabic measurement standard were used for gold Dinars and silver Drachmas. The Arabic language was also constantly used for lettering.

Another major change happened during the third century after the Arabs’ invasion. Gold Dinars minted in Iran, Iraq and also Egypt bore the place of coinage. It indicated Caliphs’ monopolization in coinage and satisfying the flourishing economies’ demands. The name of Caliphs appeared gradually on coins and Caliphate political realm of power began to be disintegrated. Anyhow, the Islamic world had reached a single economic currency freely and actually credible even in very remote areas of the Empire.

Tahirid, Saffarid and Samanid governors as well as other dynasties in Iran minted lots of coins and used them in the trade with North Europe. Admiring titles started to appear on coins to the extent that three or four titles were used on Buwayhids’ coins or the Achaemenian title of “King of Kings ” was used on Daylamites’ coins.

Seljuks minted remarkably precise and well-decorated gold coins for some time, but later the precision and uniformity and even credibility of coins began to undergo a drastic decline. During 130 years after the death of Sanjar at 1156, no coins were minted even in very active mint houses in Esfehan or Rey.

After Mongols’ invasion, some pictorial and non-pictorial coins were minted in silver. In addition, the language and writing system of Mongols were used beside Arabic ones.

During Timurids and after them, the date of coinage was being mentioned not in words, but in numbers.

Safavid period was the time of revival and promotion of the highest characteristics used in coinage like quality, art, legibility, design and above all, the Farsi language. Safavid government minted gold Ashrafy and silver Abbasy coins in compliance with Duka currency in use in Venice. Later, Nader Shah, Afsharid king, ordered some gold Mohr and silver Rupee coins to be minted based on the monetary system of India.

There were not any pictures on early Qajar coins, but they later added them to their coins.

After more than half a century, Reza Shah’s profile appeared with an aigretted hat on gold coins in 1926. A few years before him, during the last Qajar king, Mohammad Shah, the national flag emblem of “Red Lion and Sun” appeared on the front of coins for the first time.

During Pahlavis, this pattern was combined either with the king’s face or an inscription certainly commemorative of the first time coinage started in the Persian Empire.